The Art of Love

by Nicola Dale and Adam Smyth

In 2018, Nicola presented her solo exhibition ‘The Things That Look Back’ at the Portico Library, in collaboration with the Warburg Institute and the John Rylands Library. Read more here.

Please note: this article contains strong language.

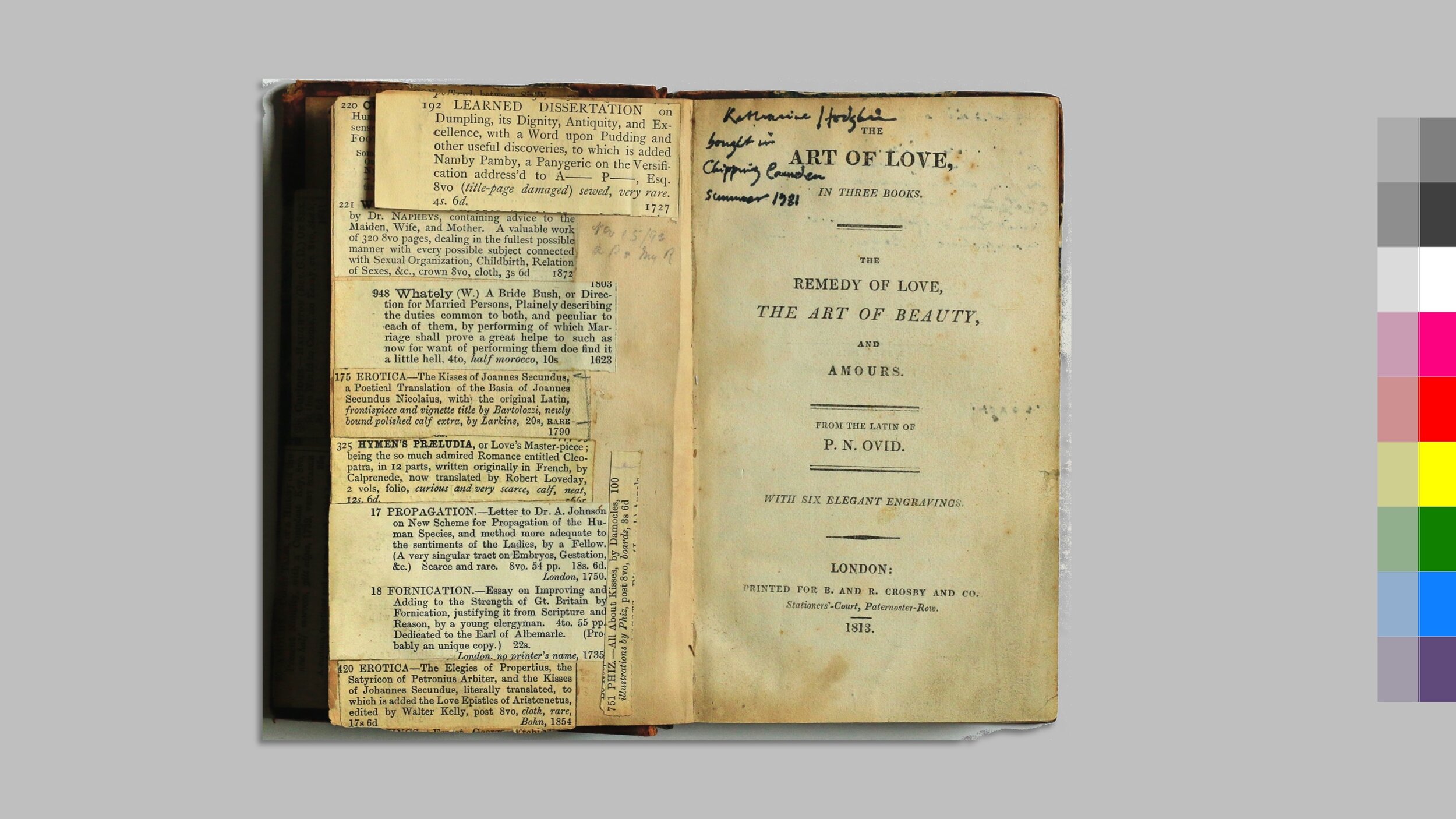

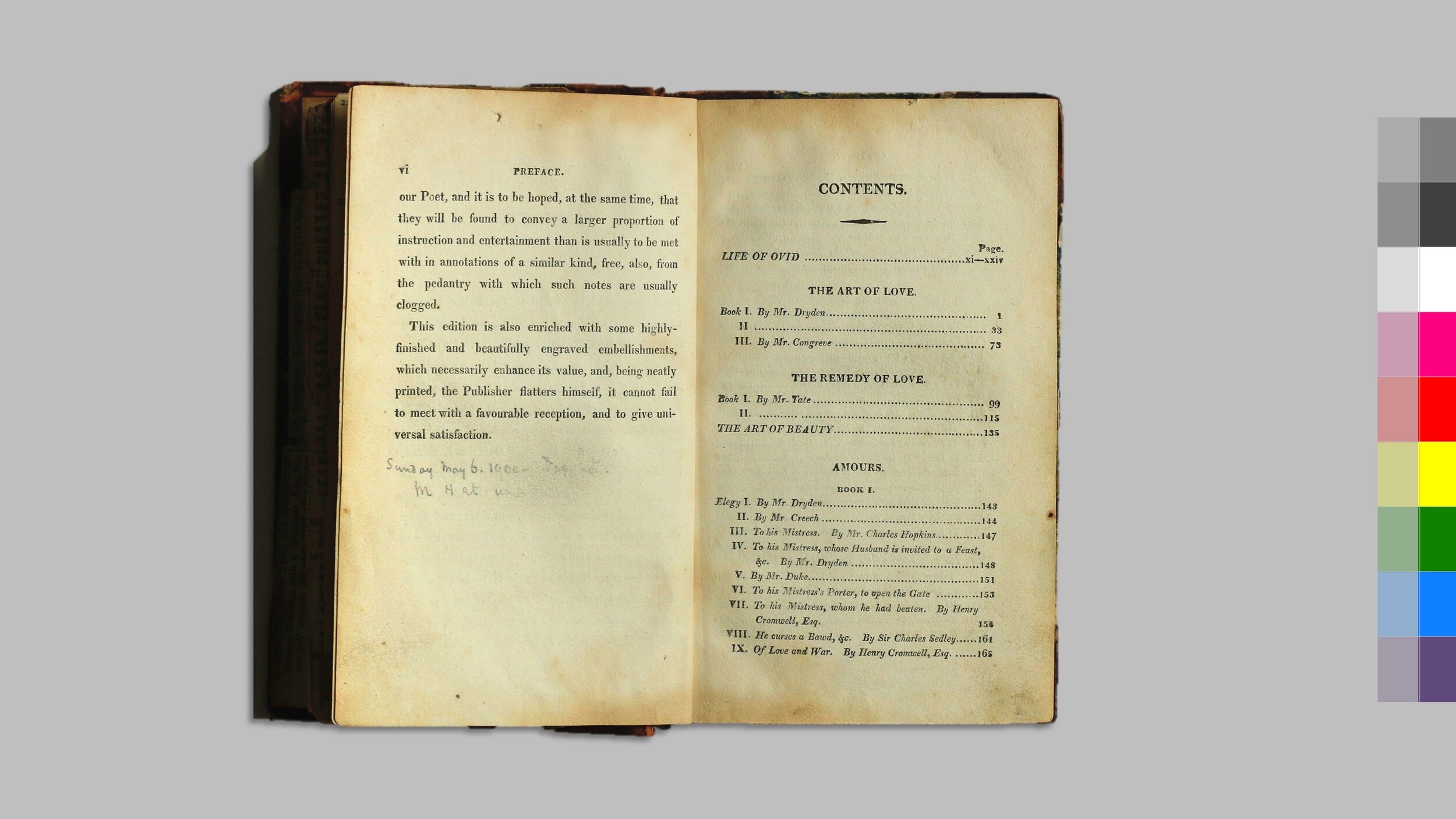

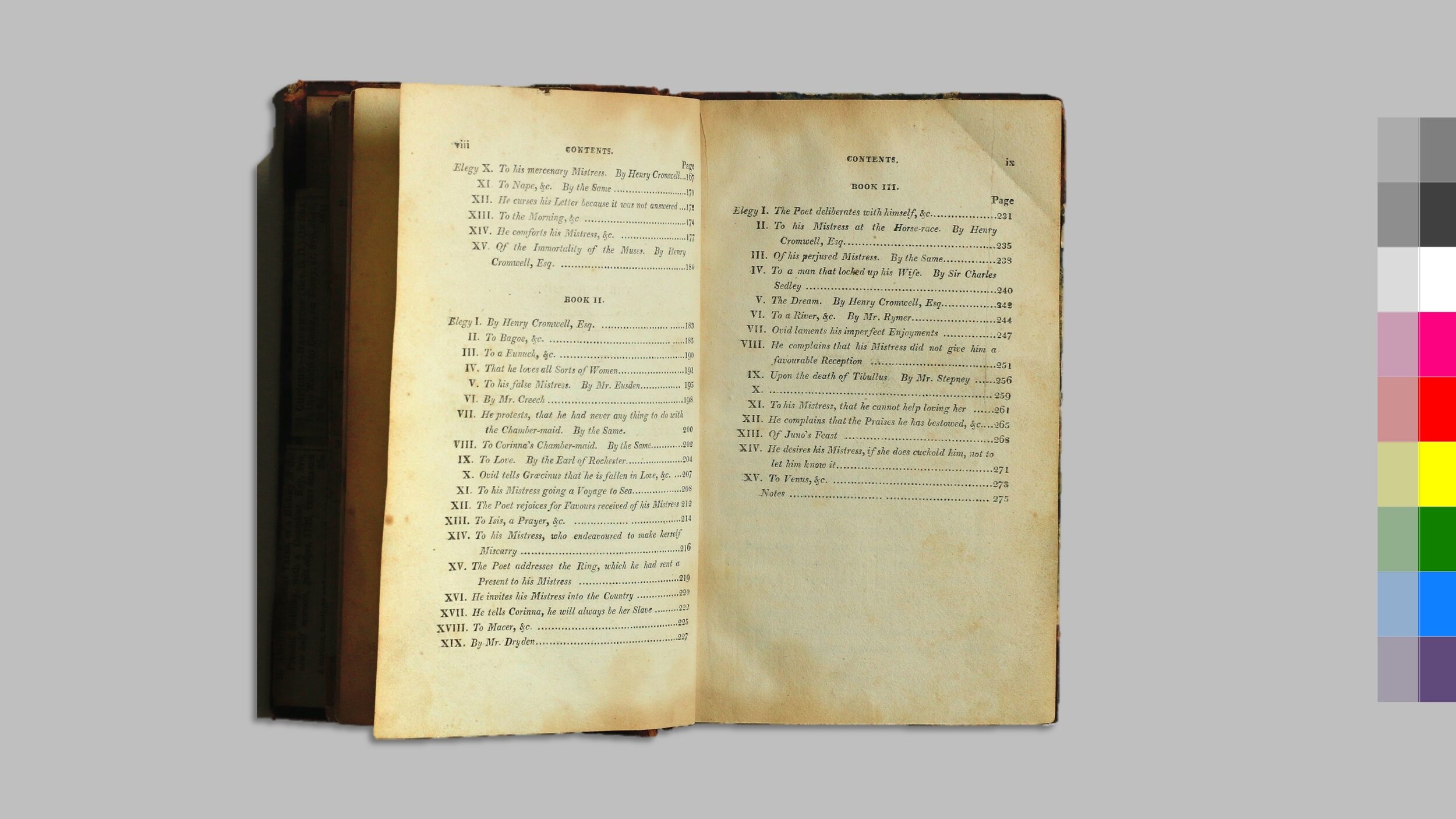

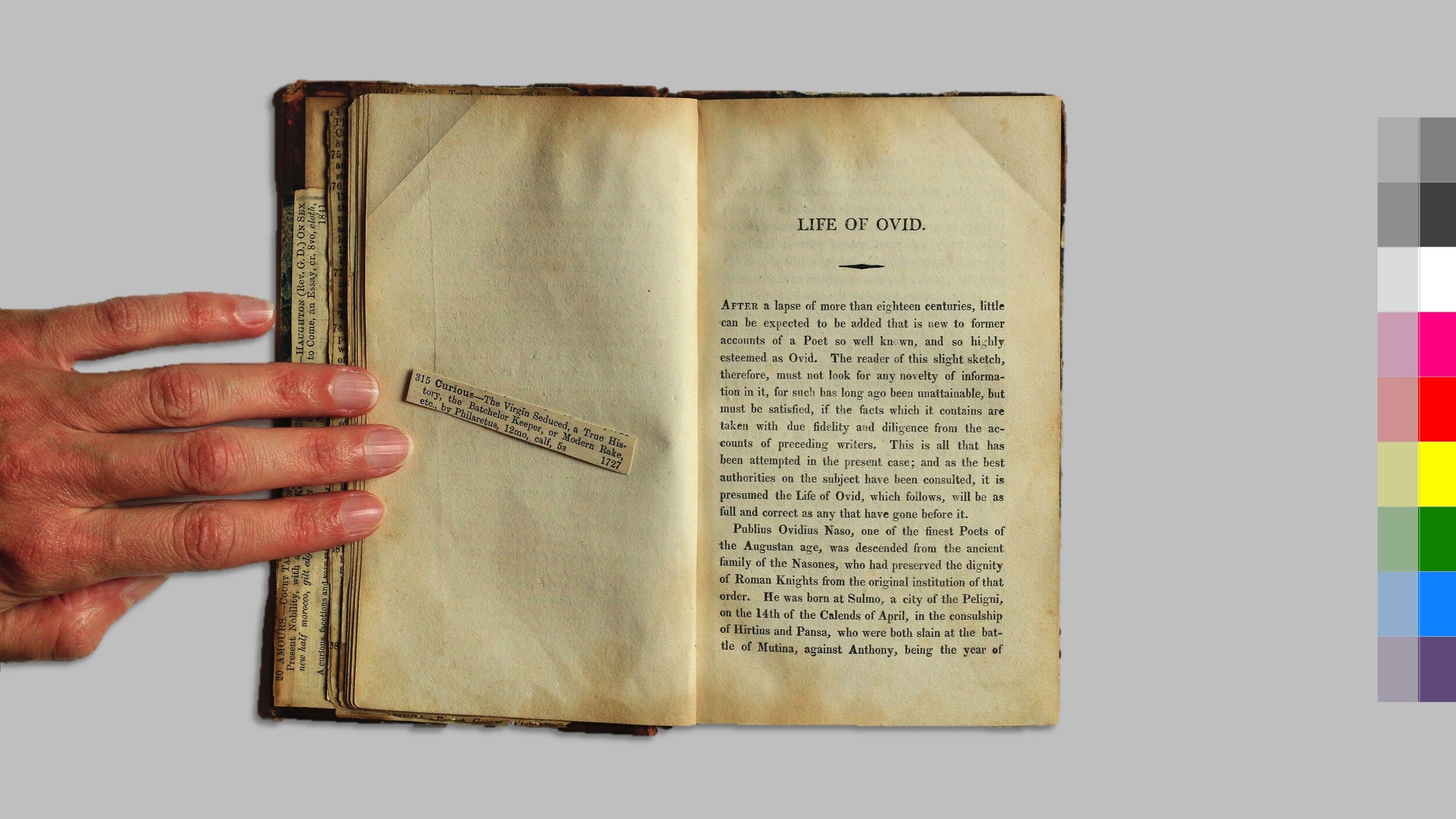

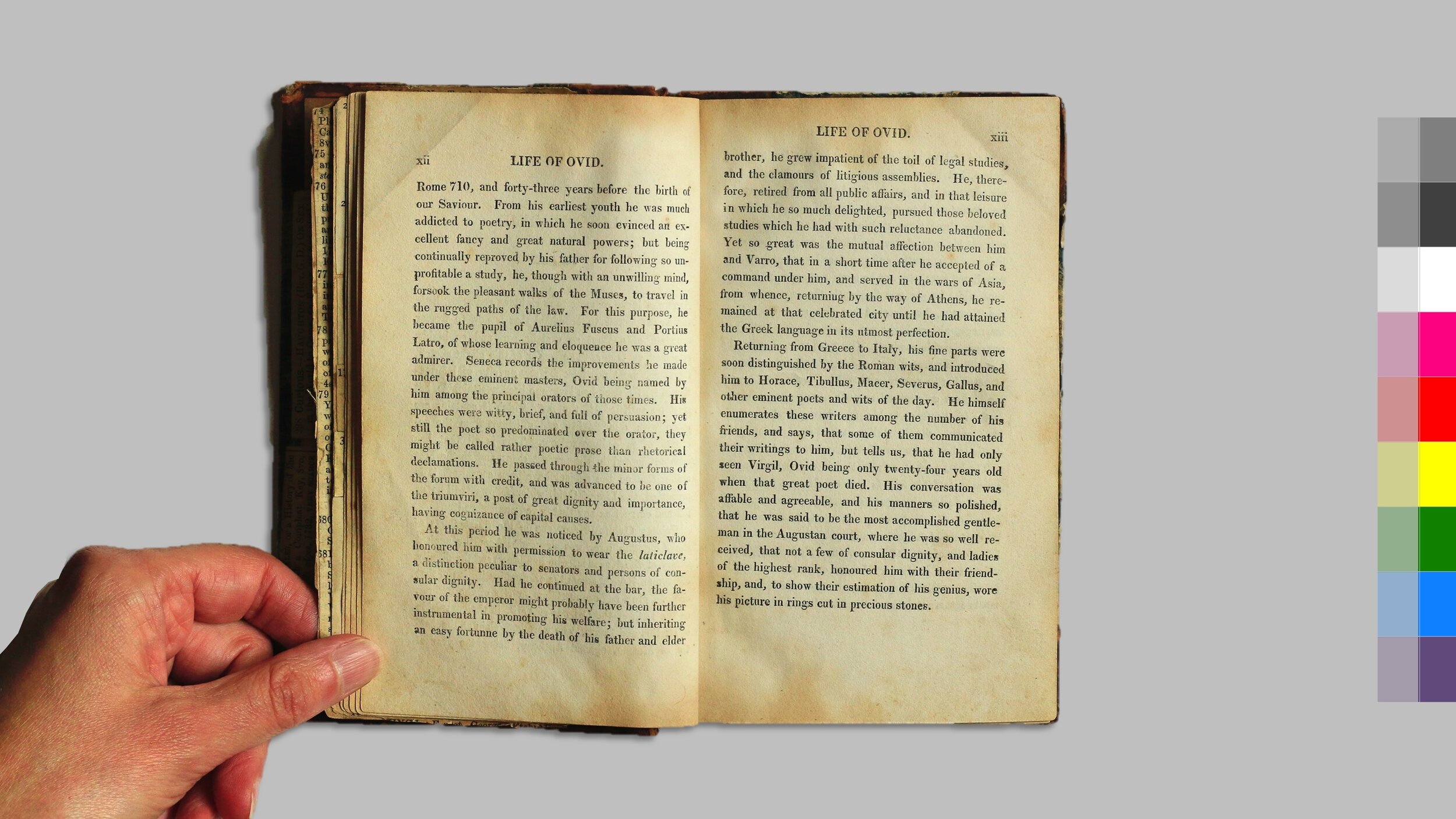

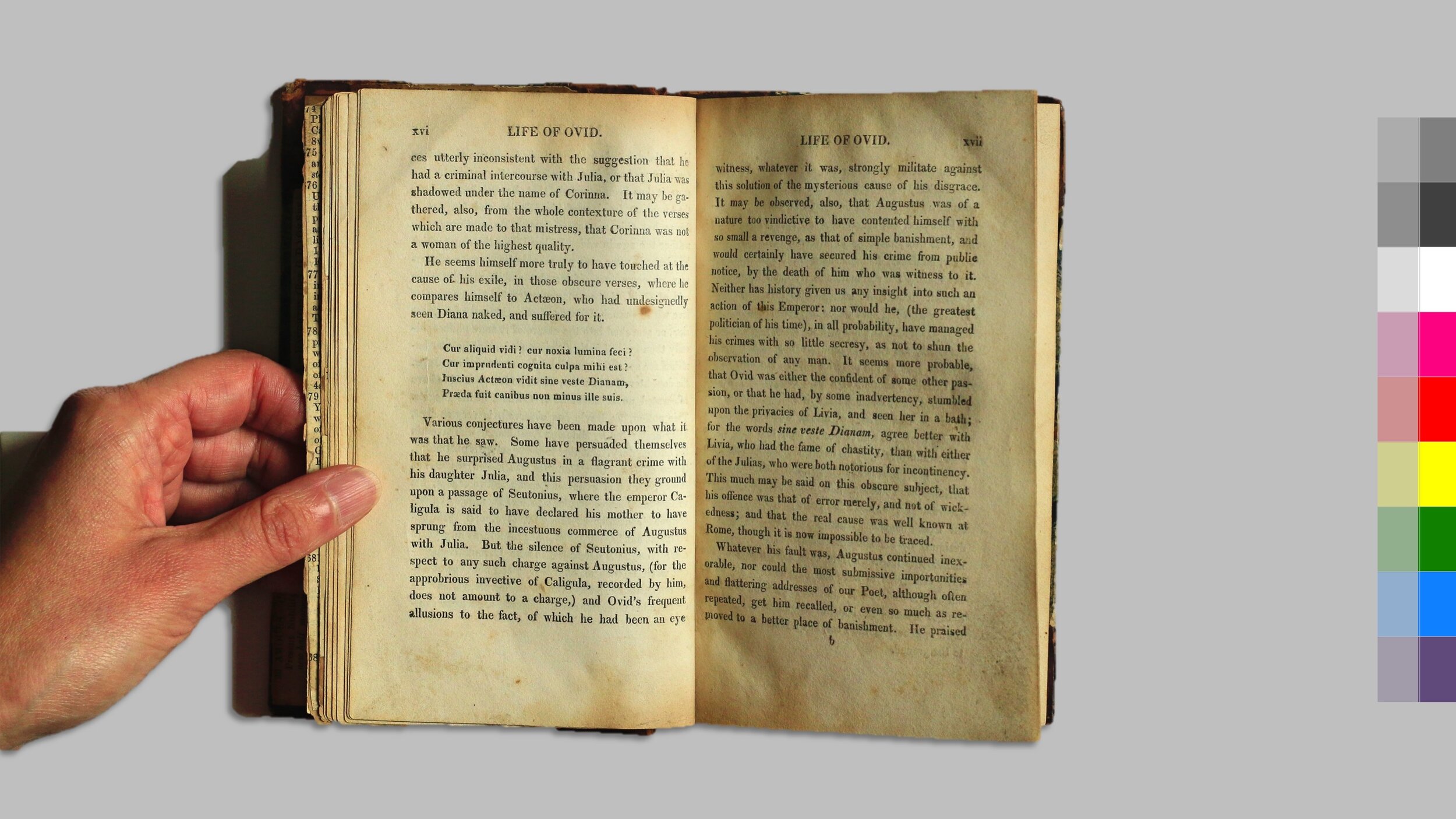

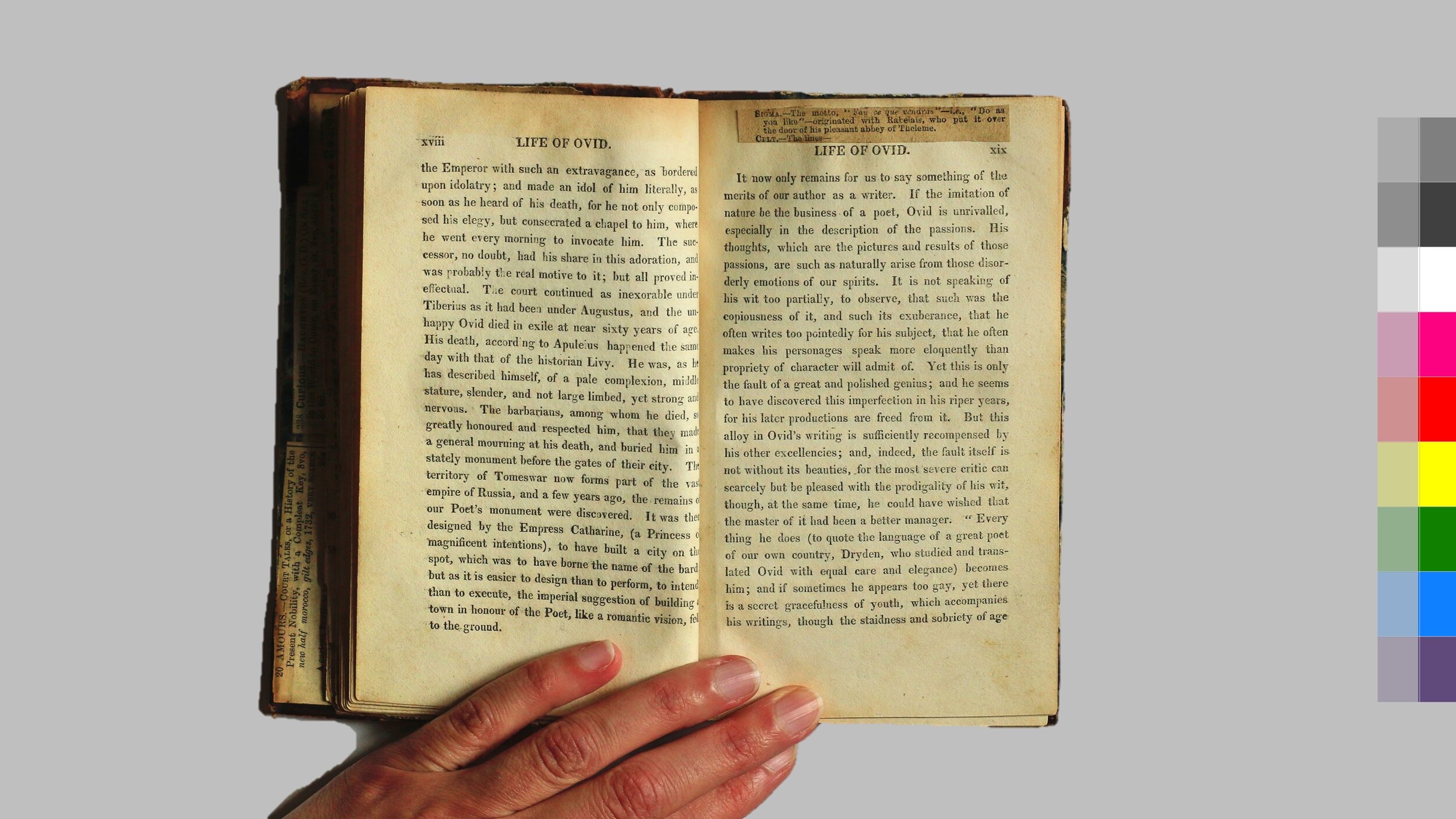

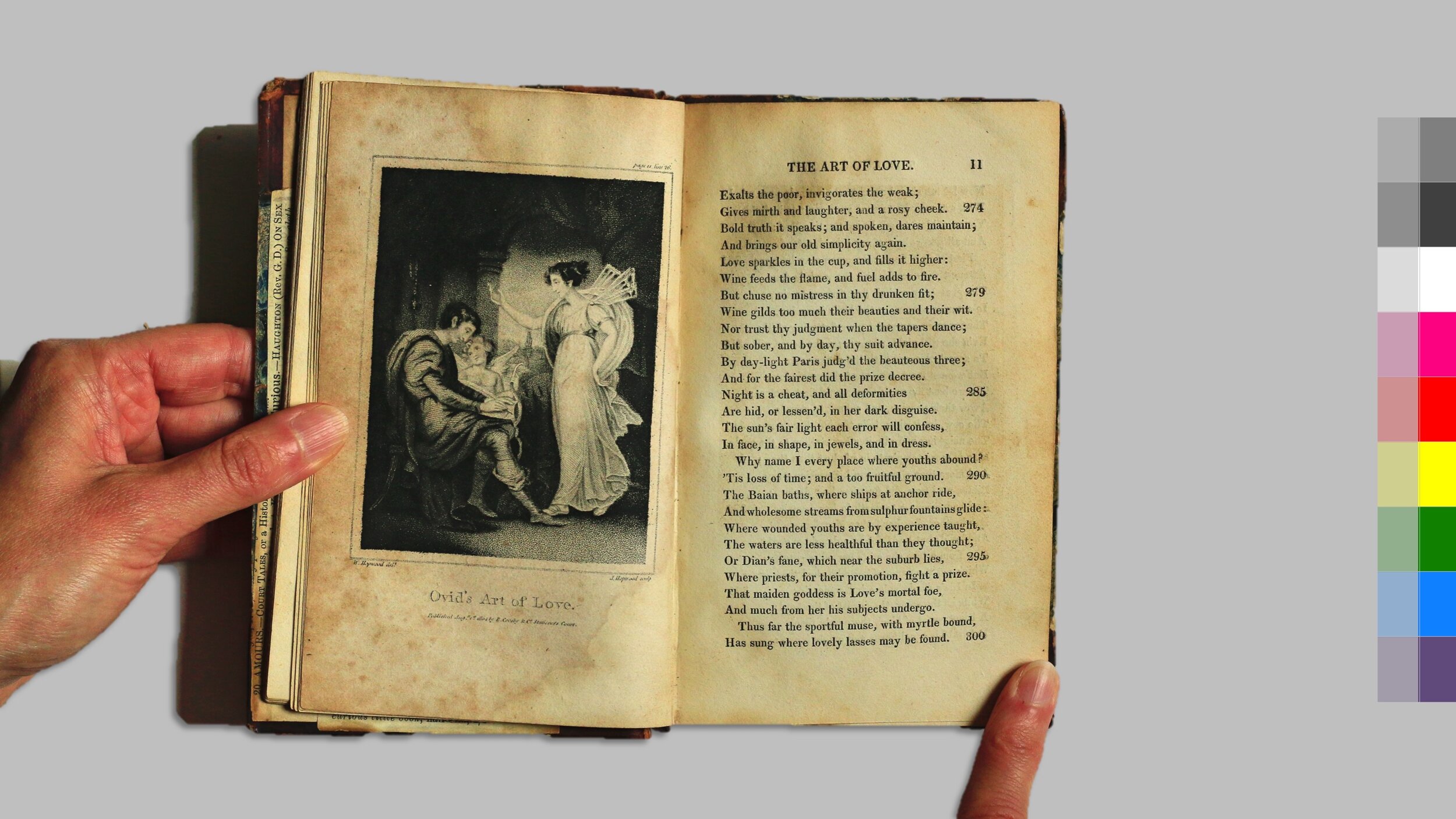

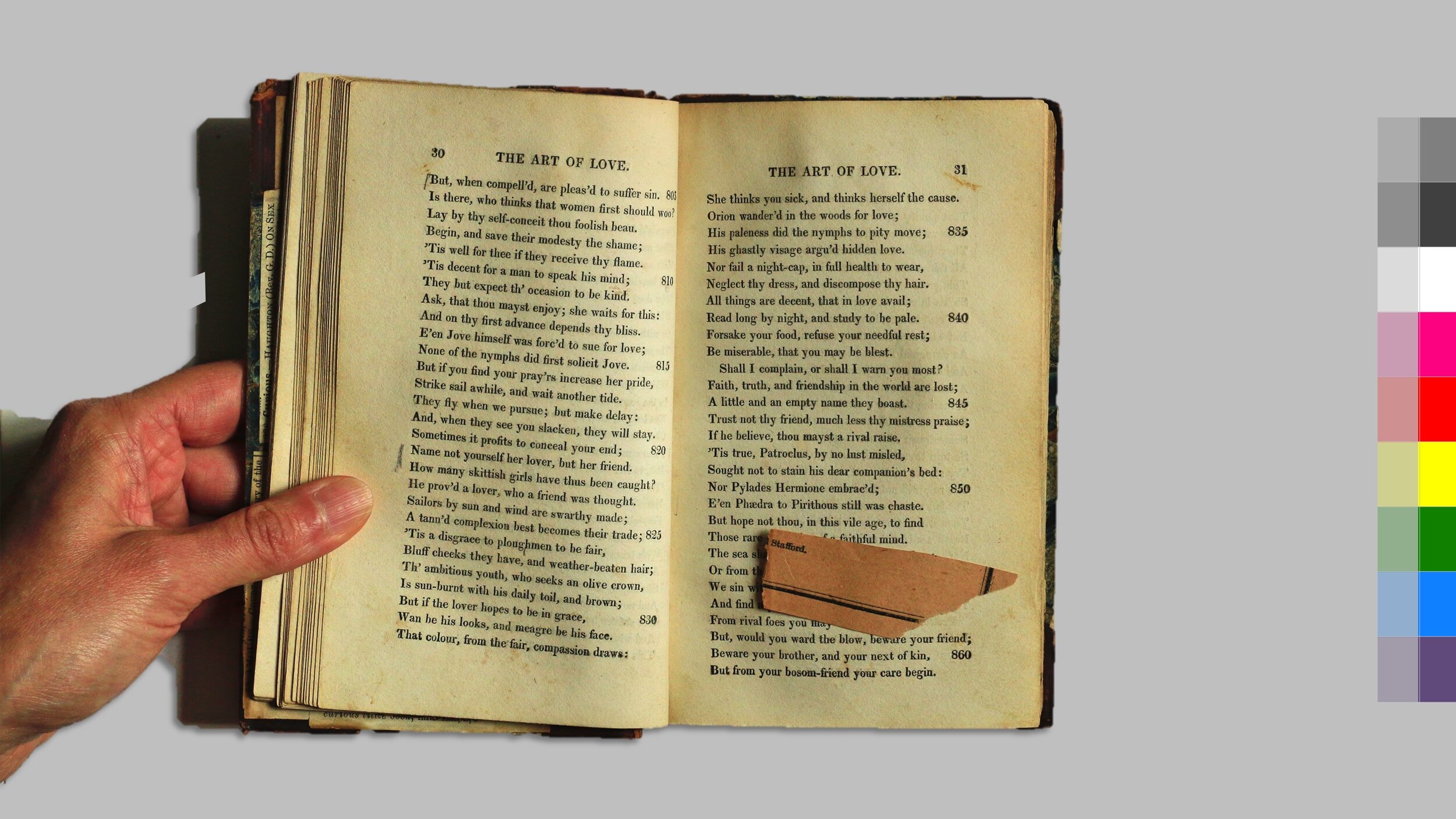

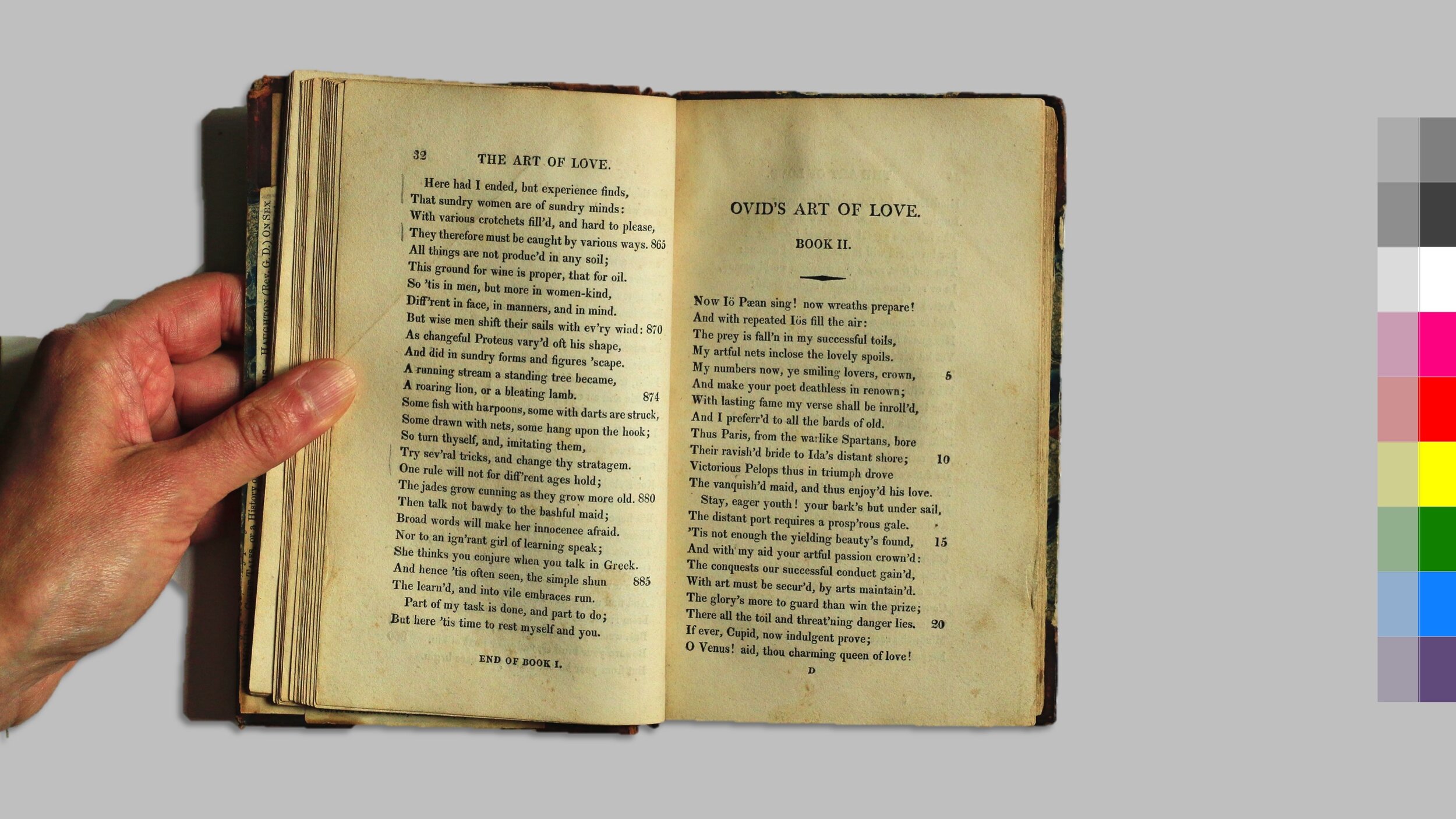

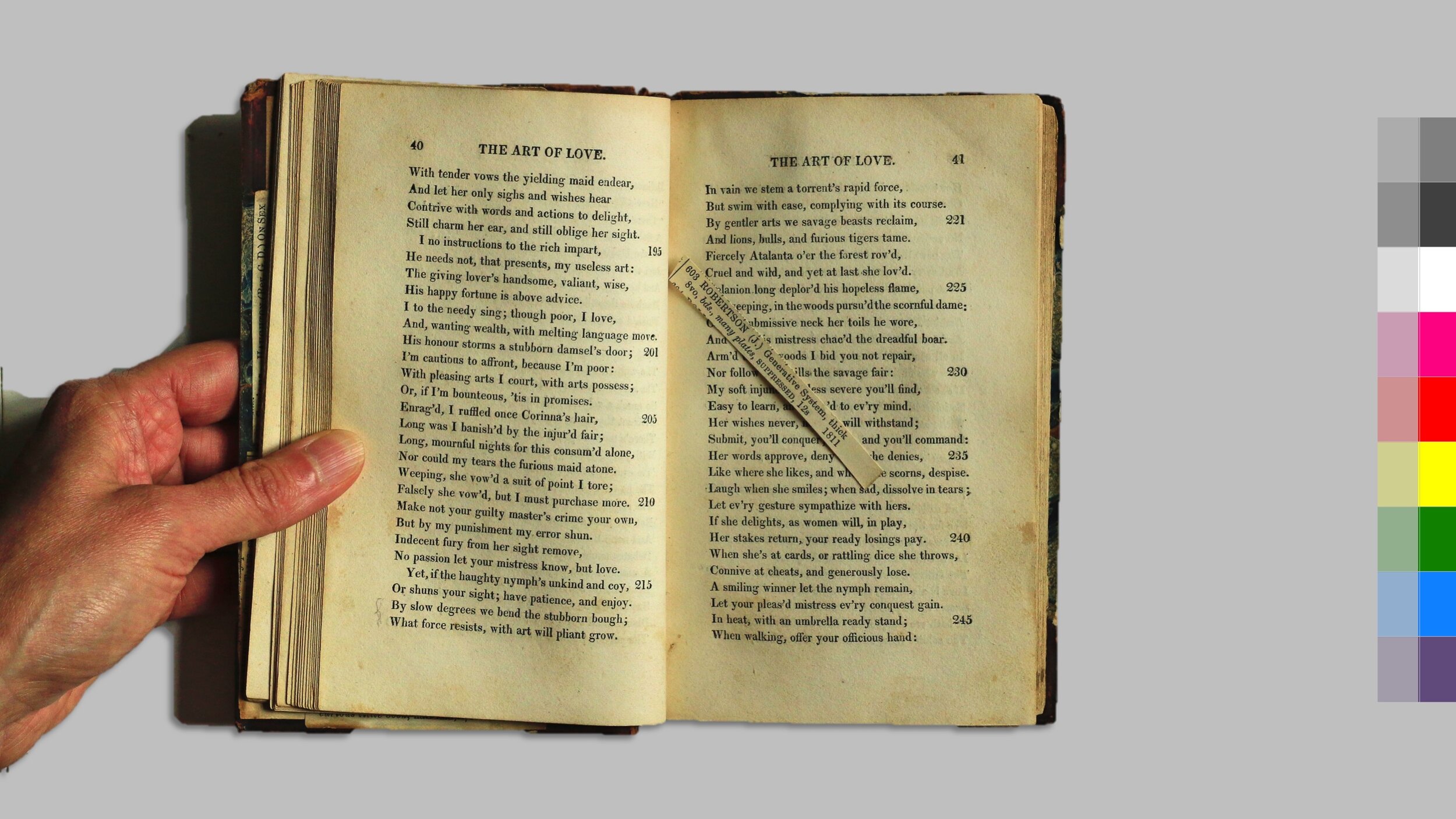

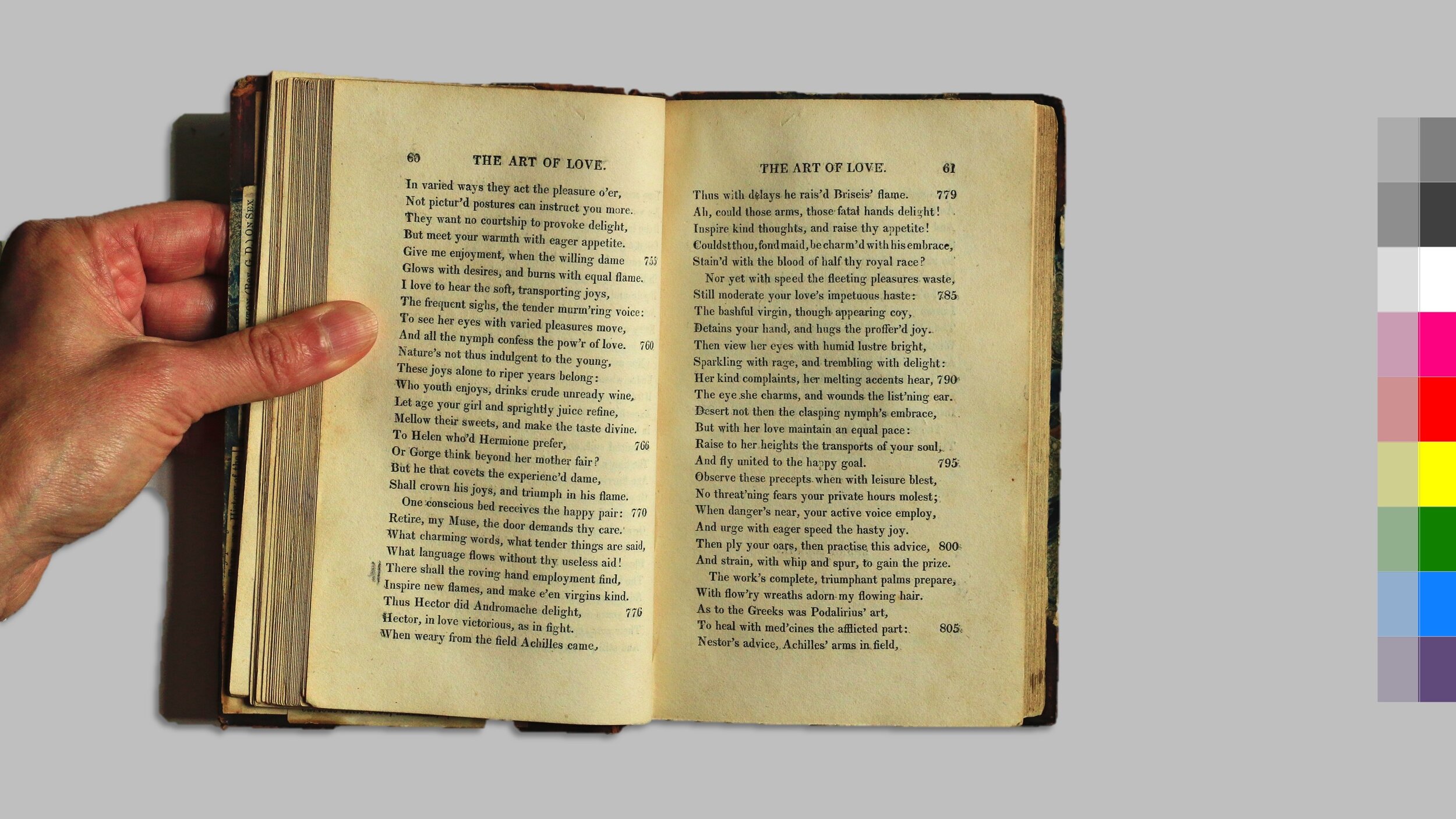

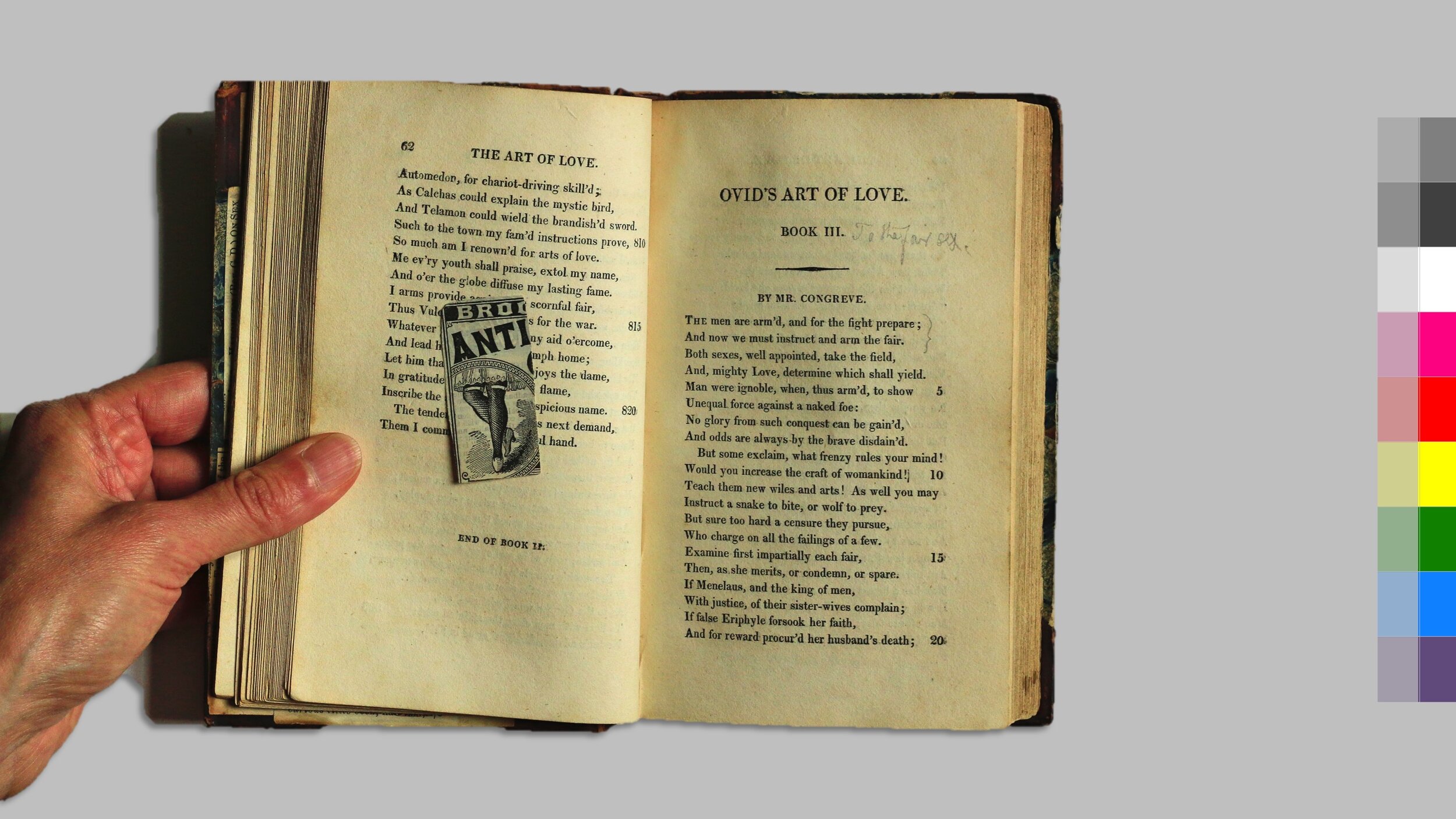

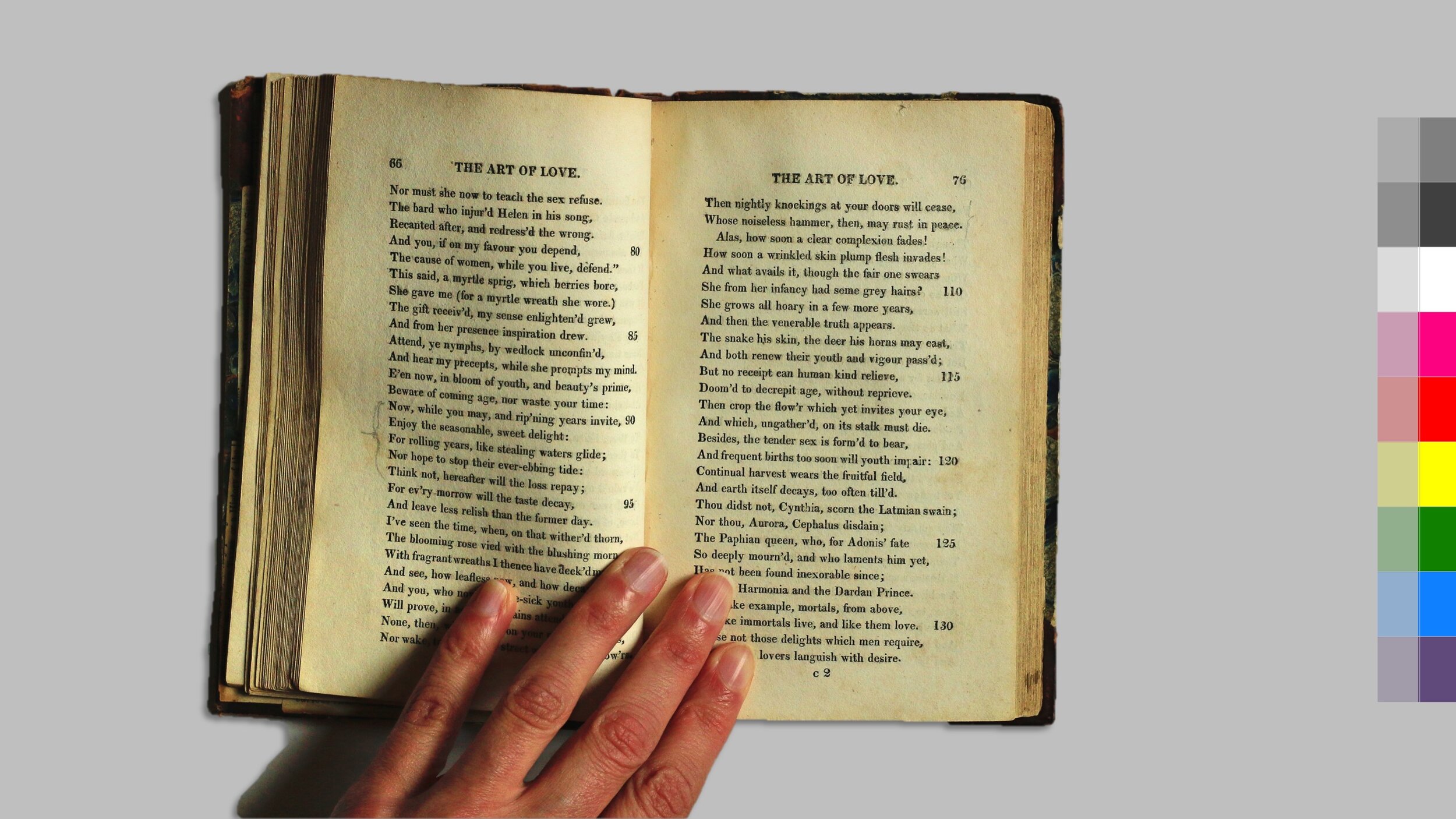

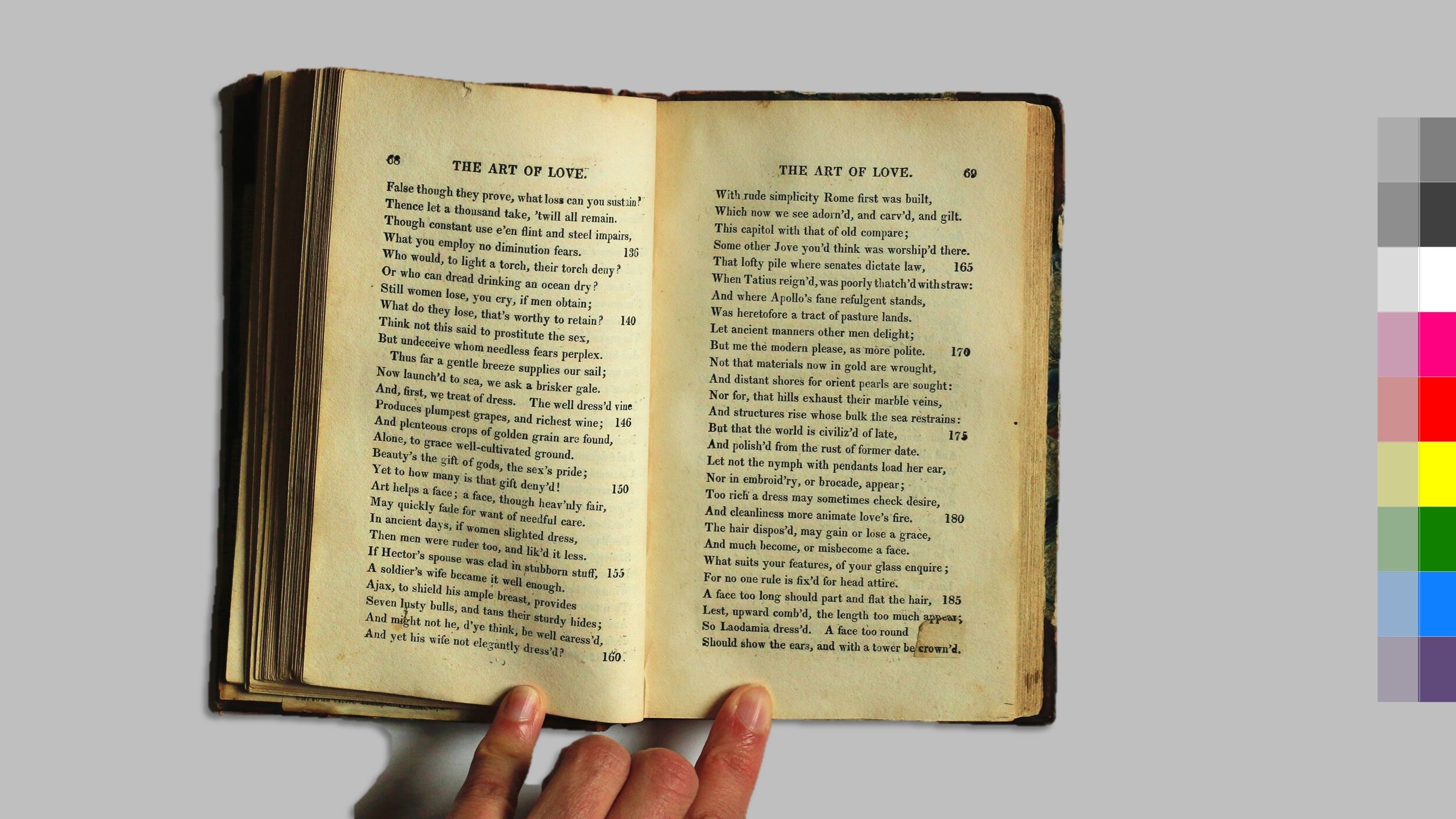

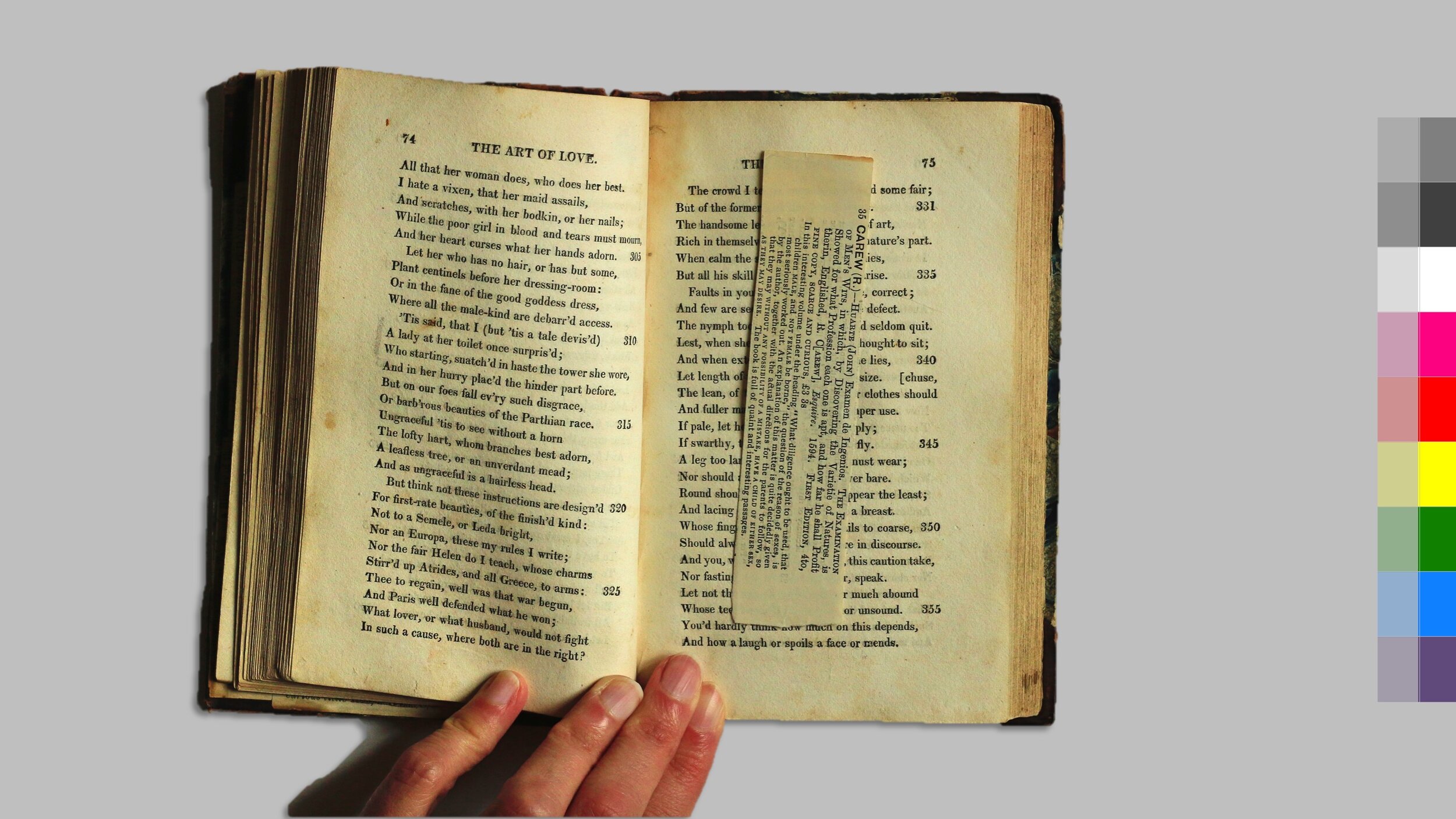

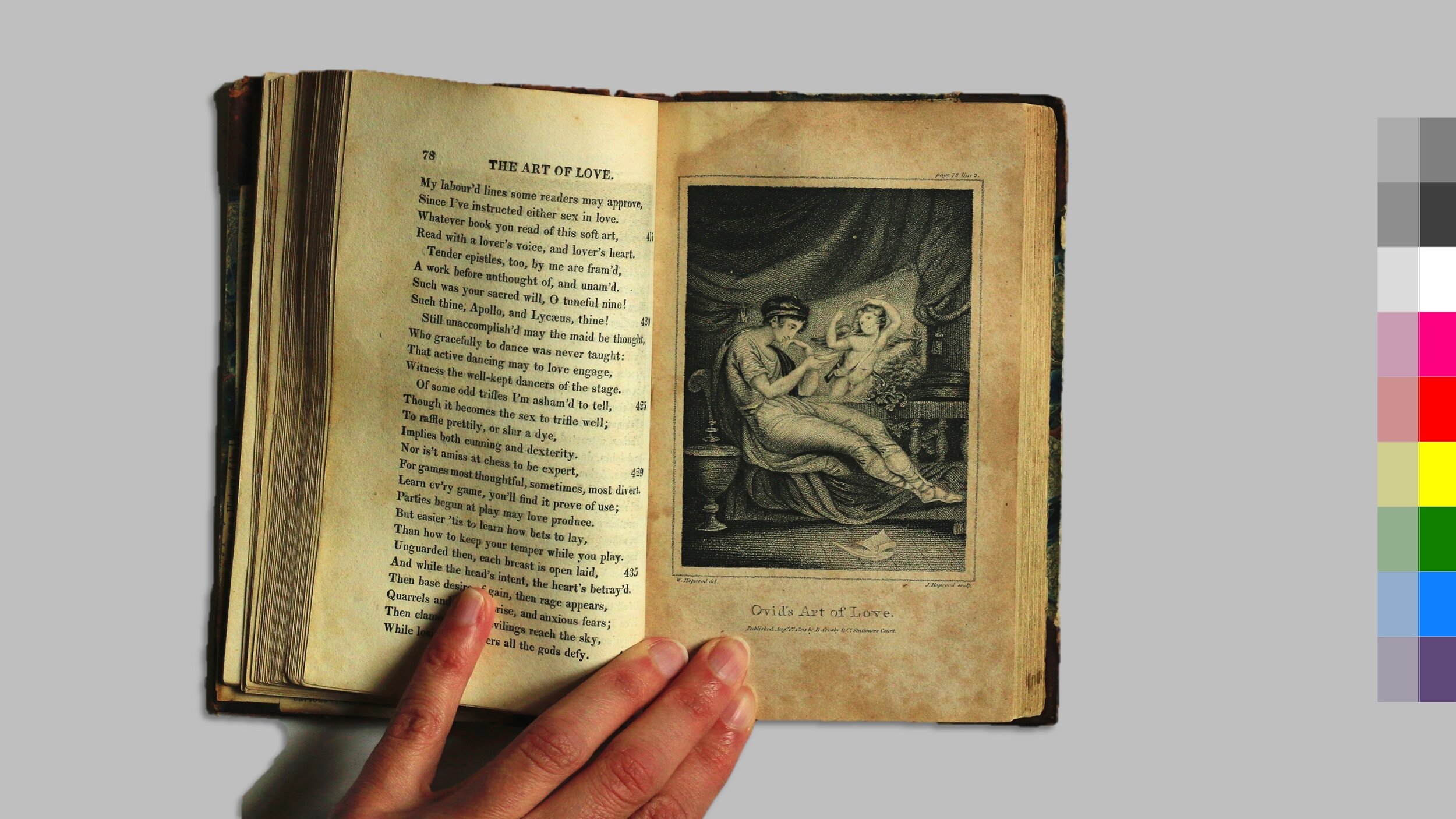

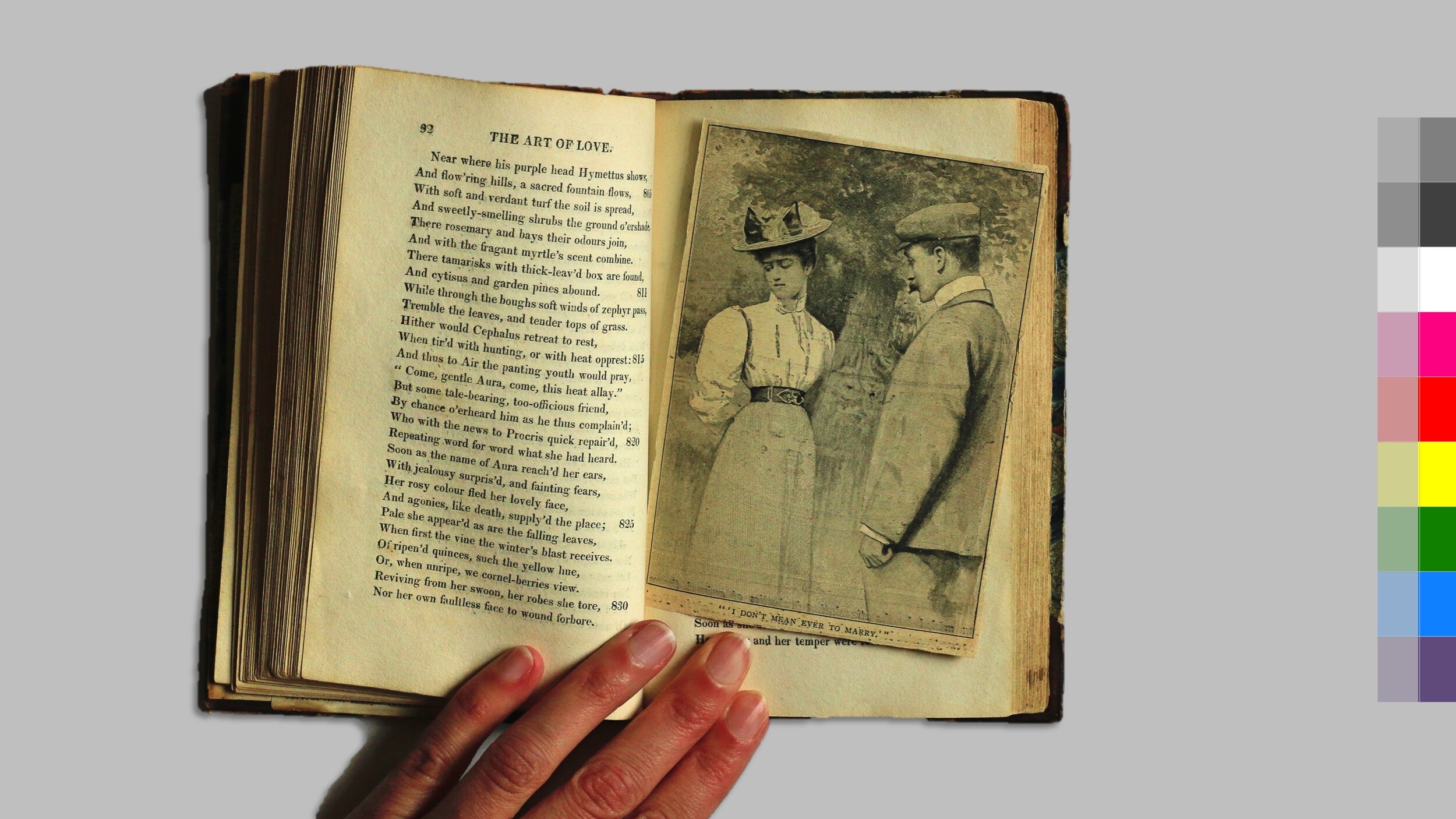

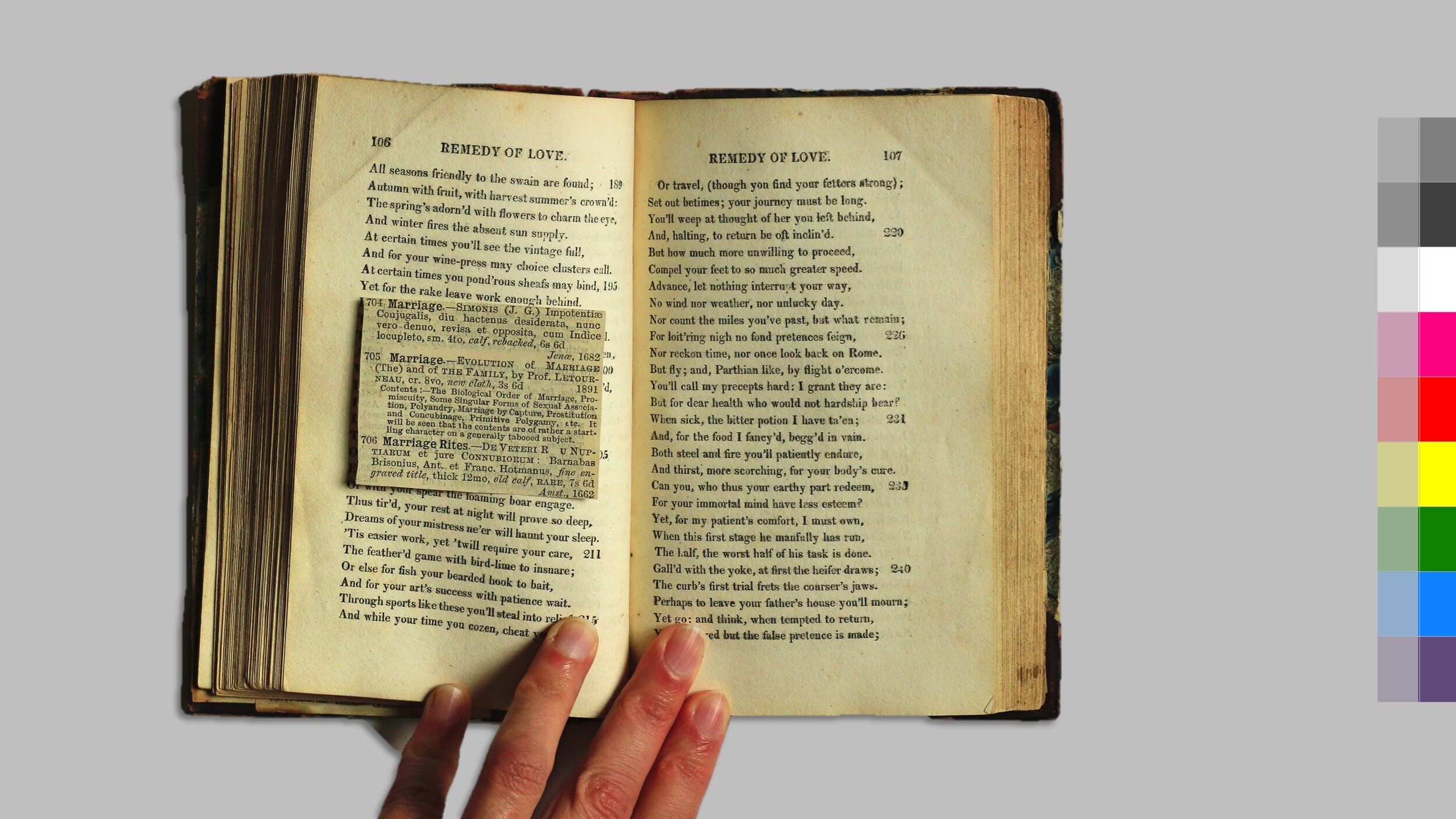

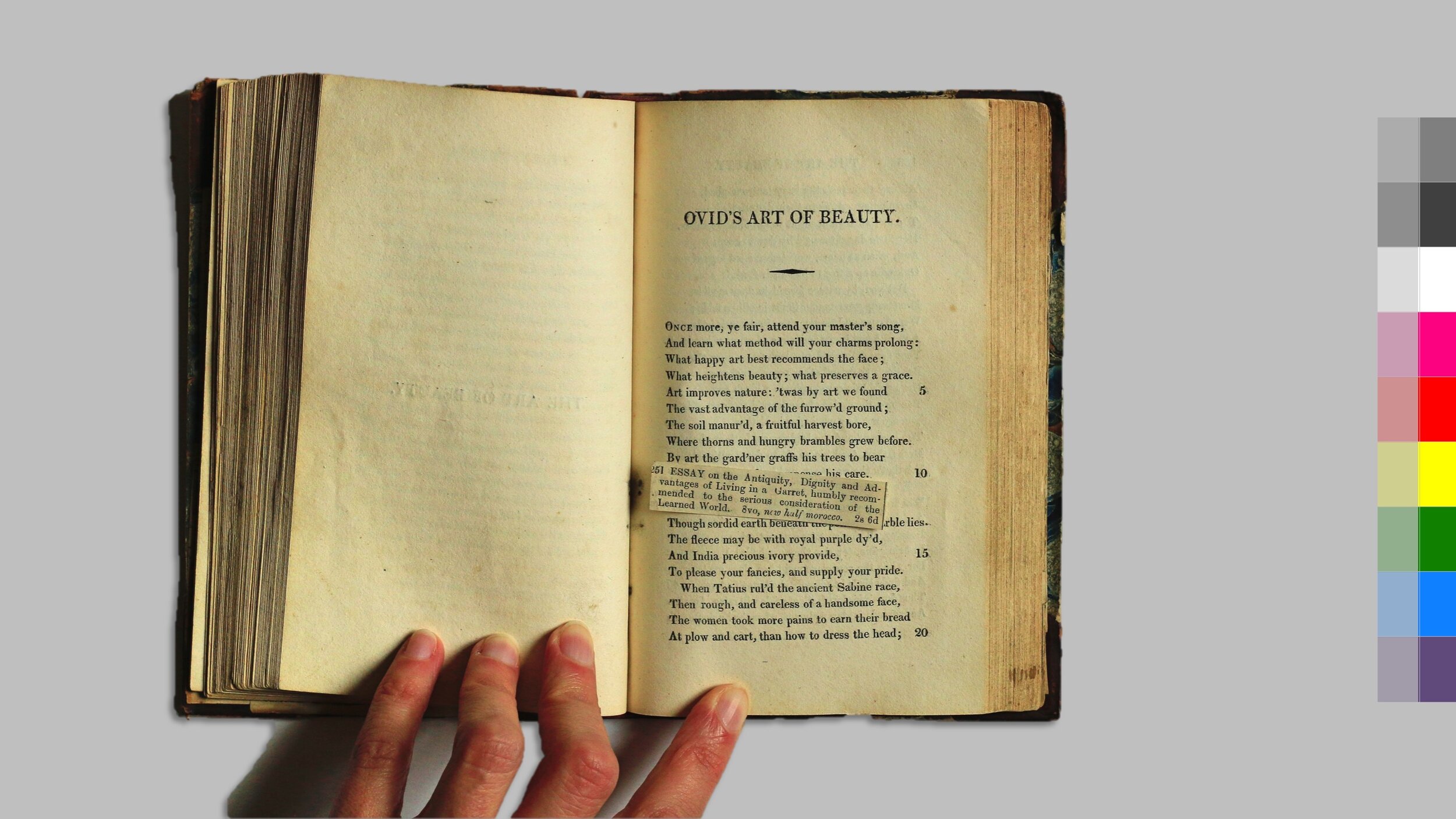

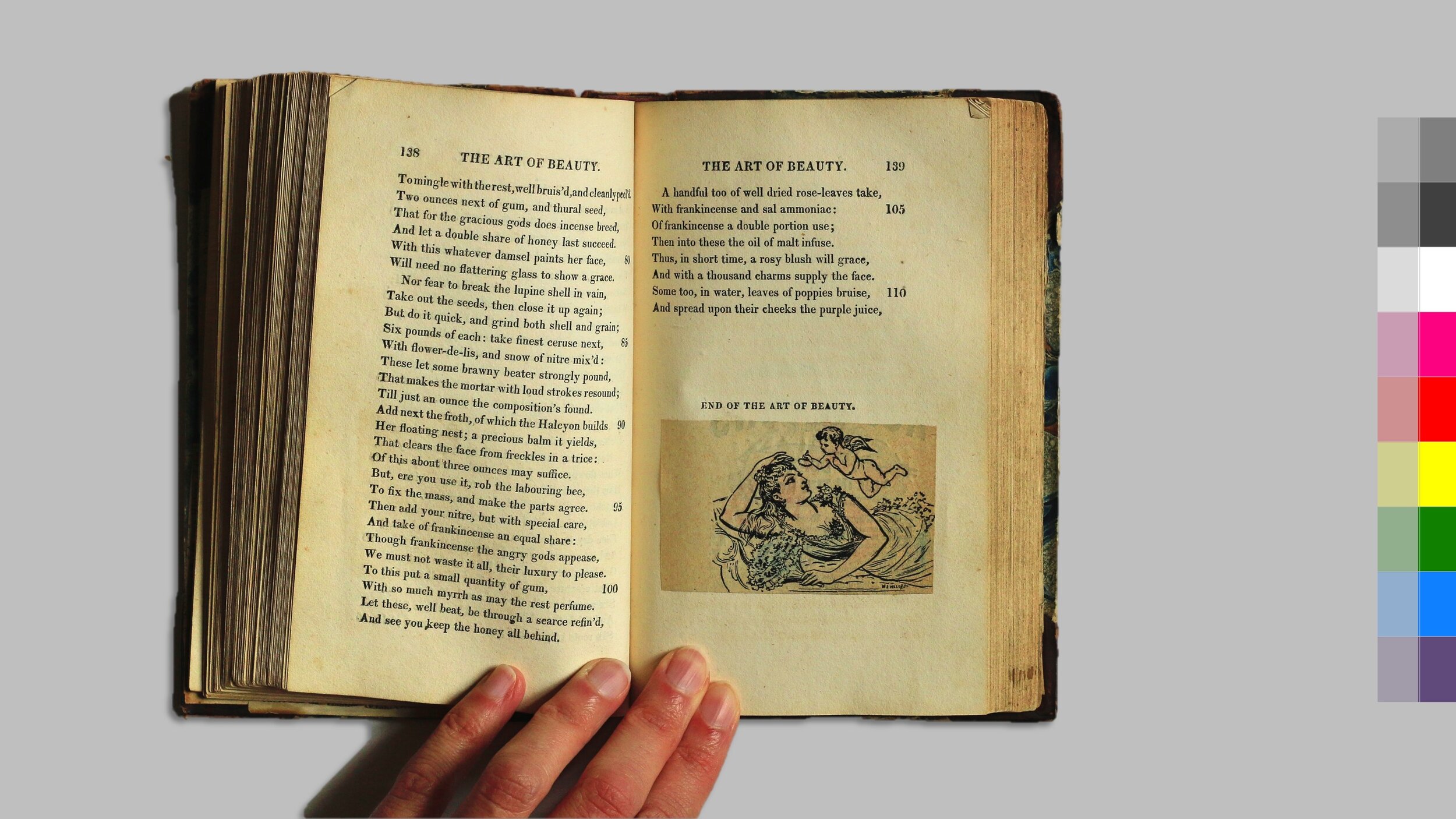

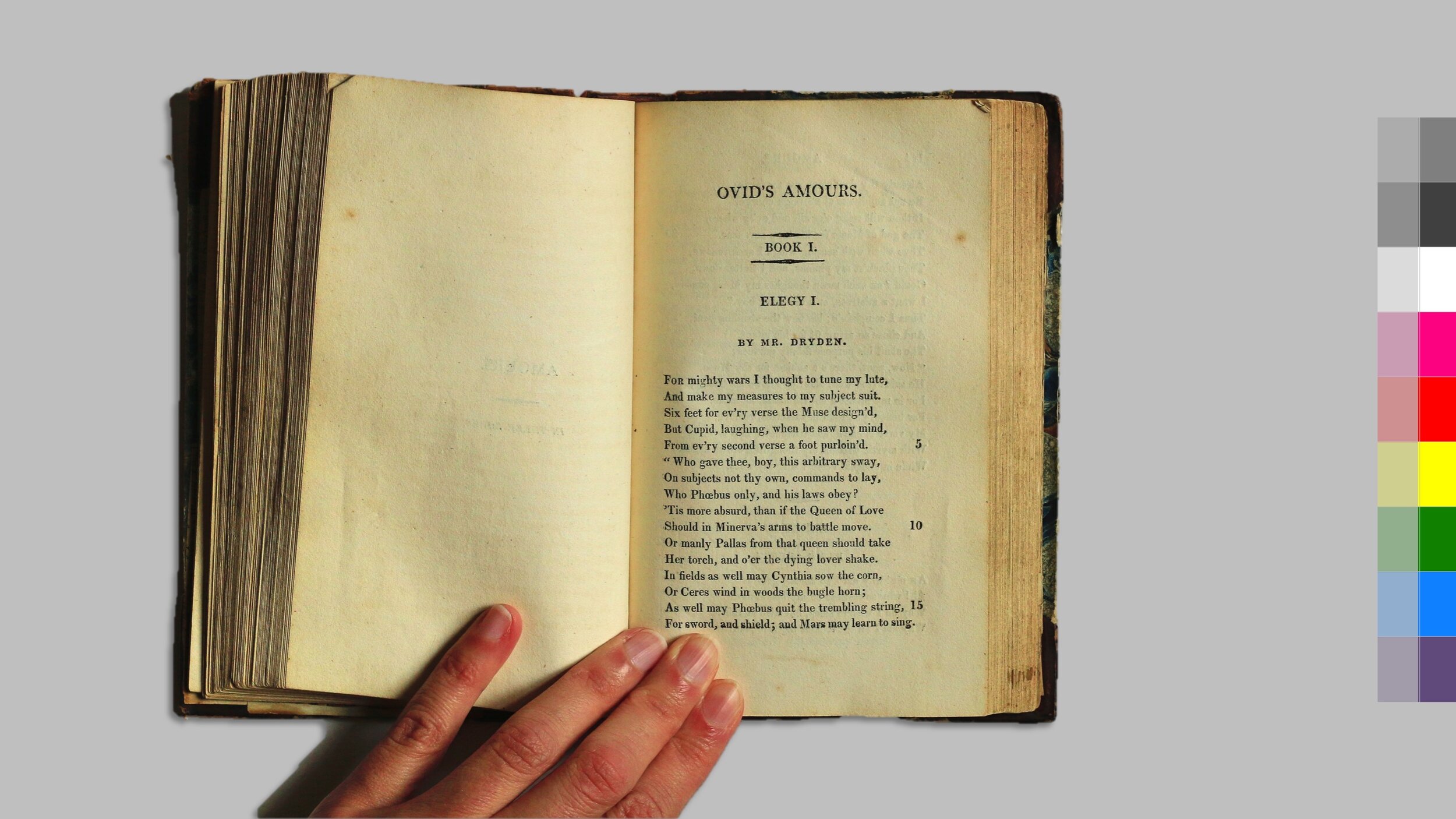

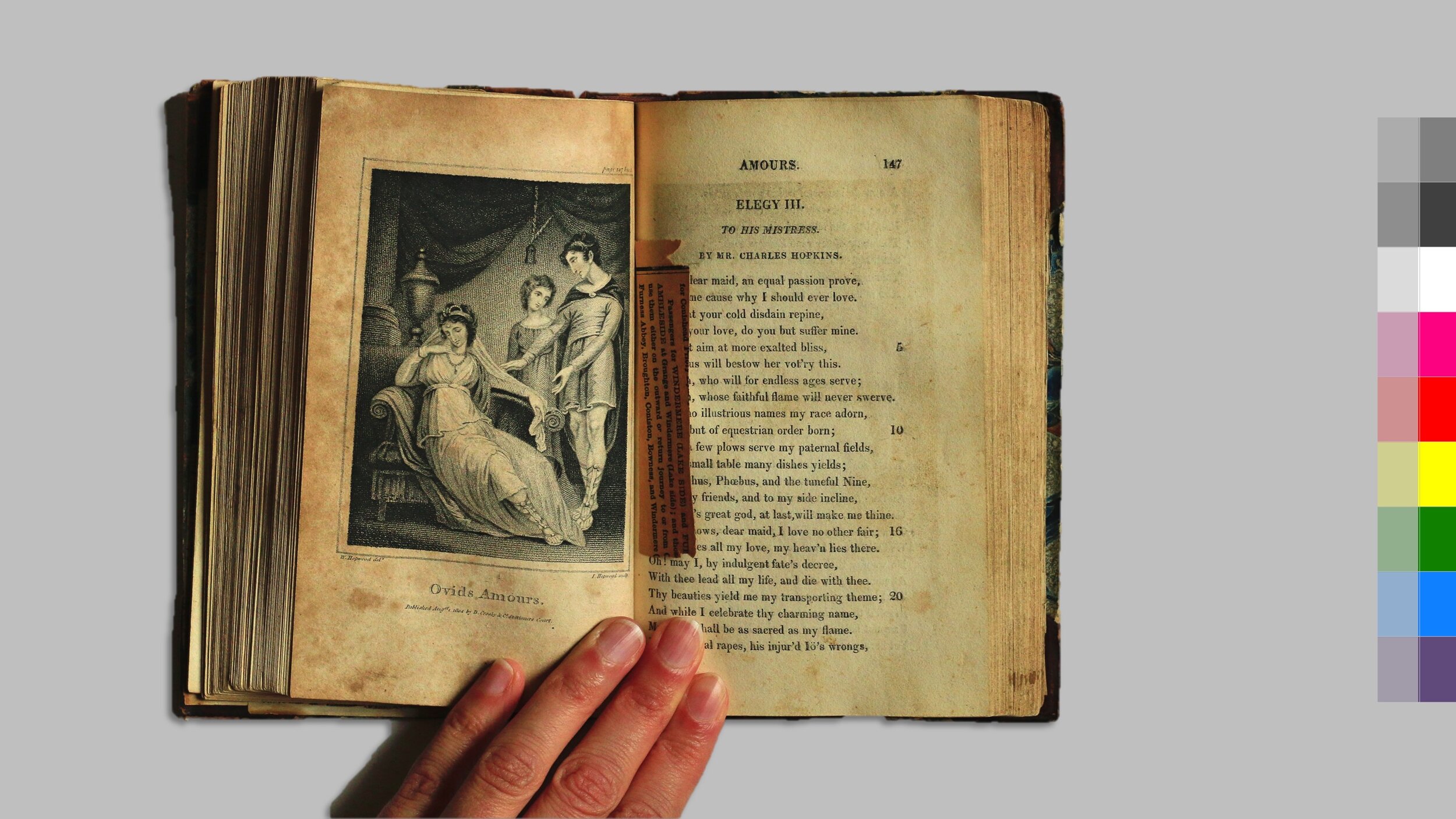

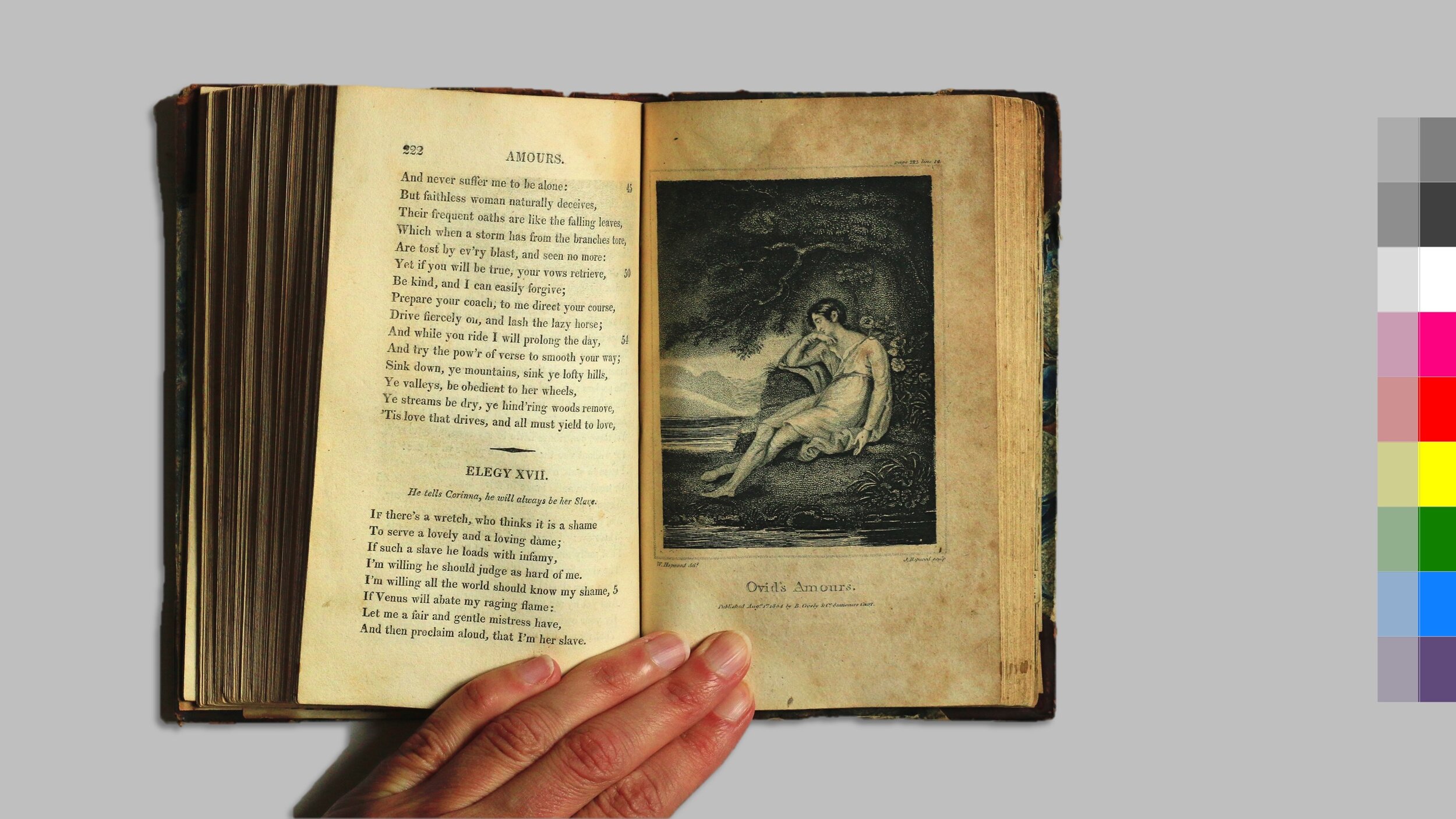

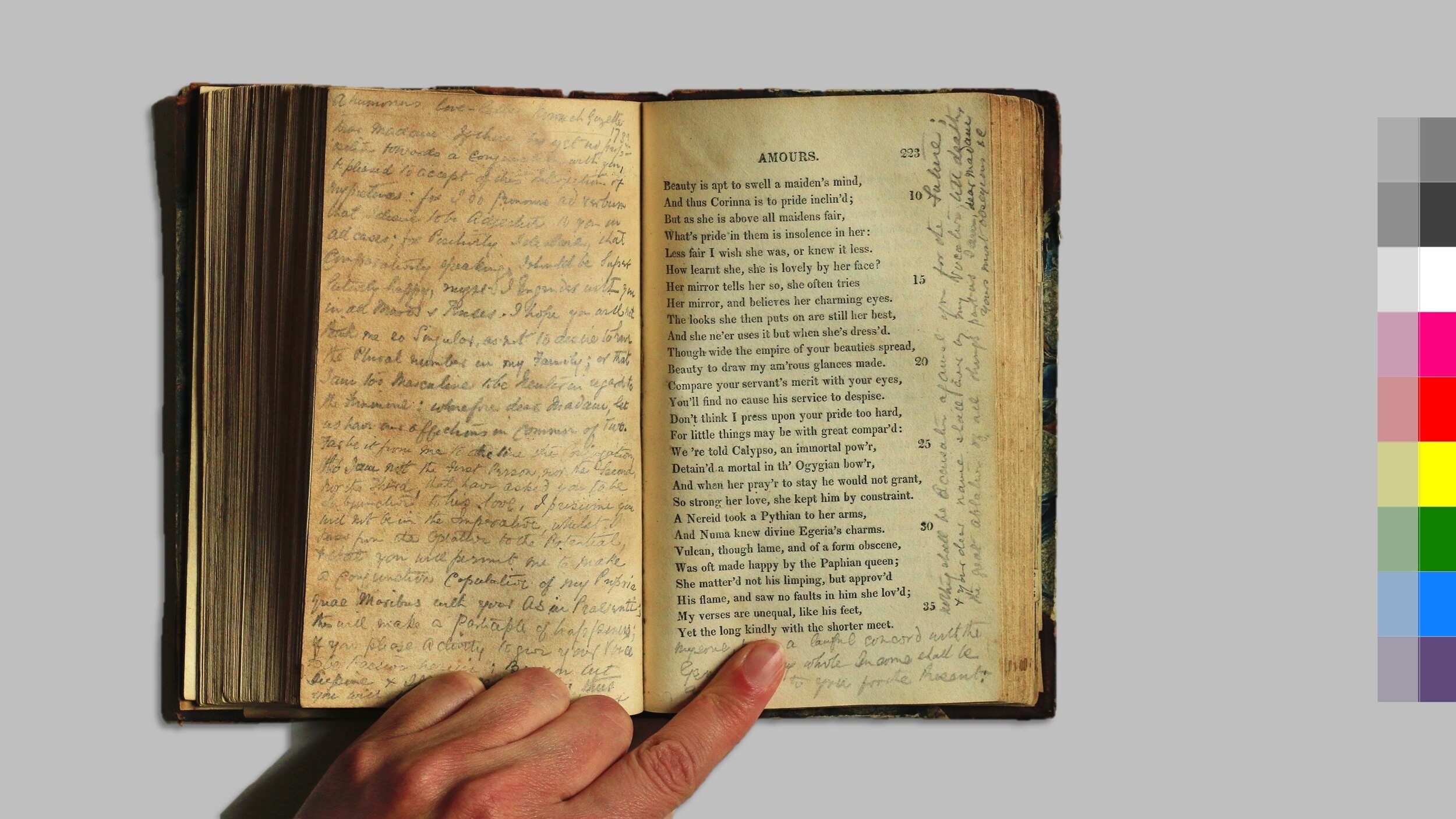

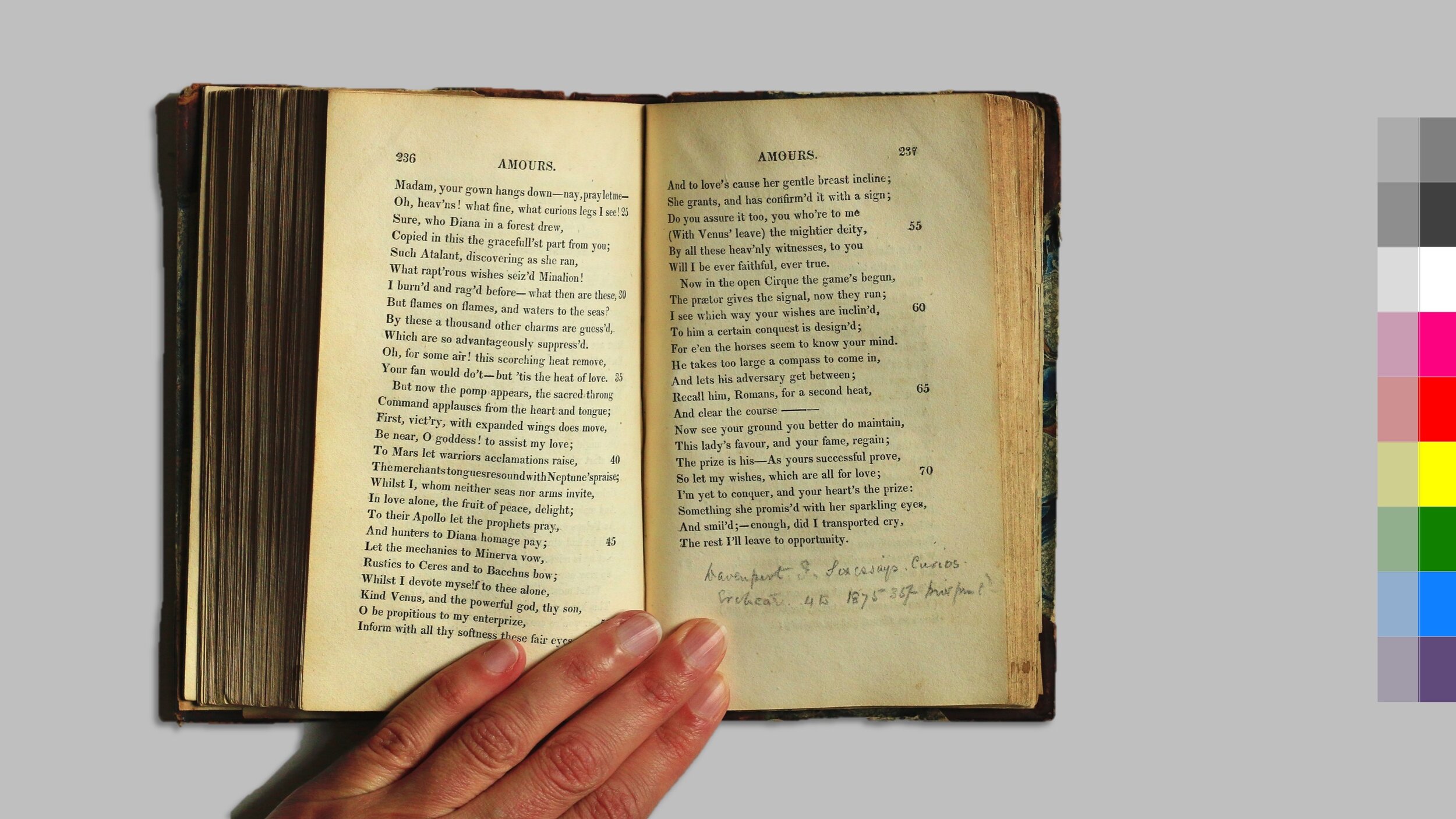

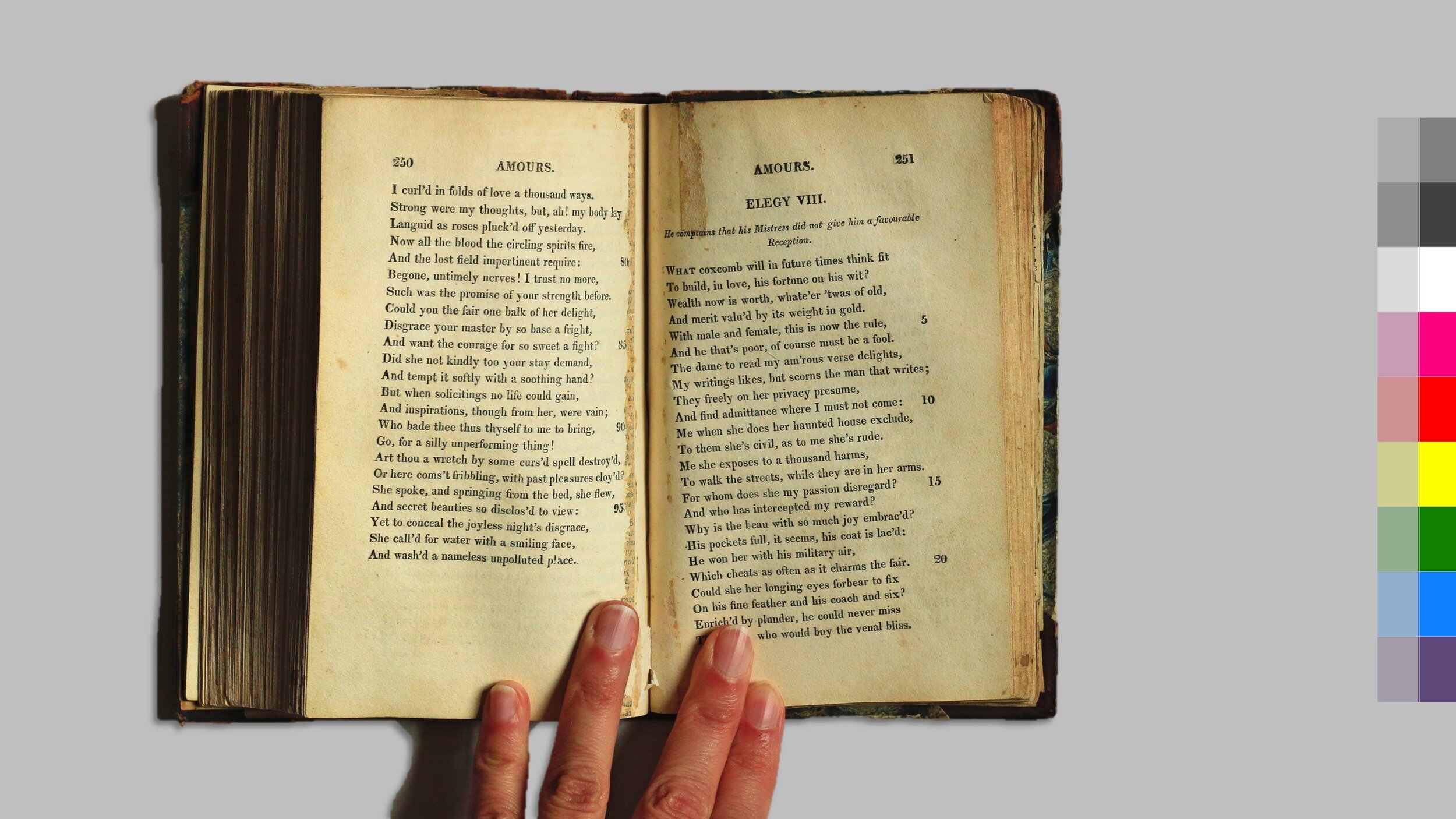

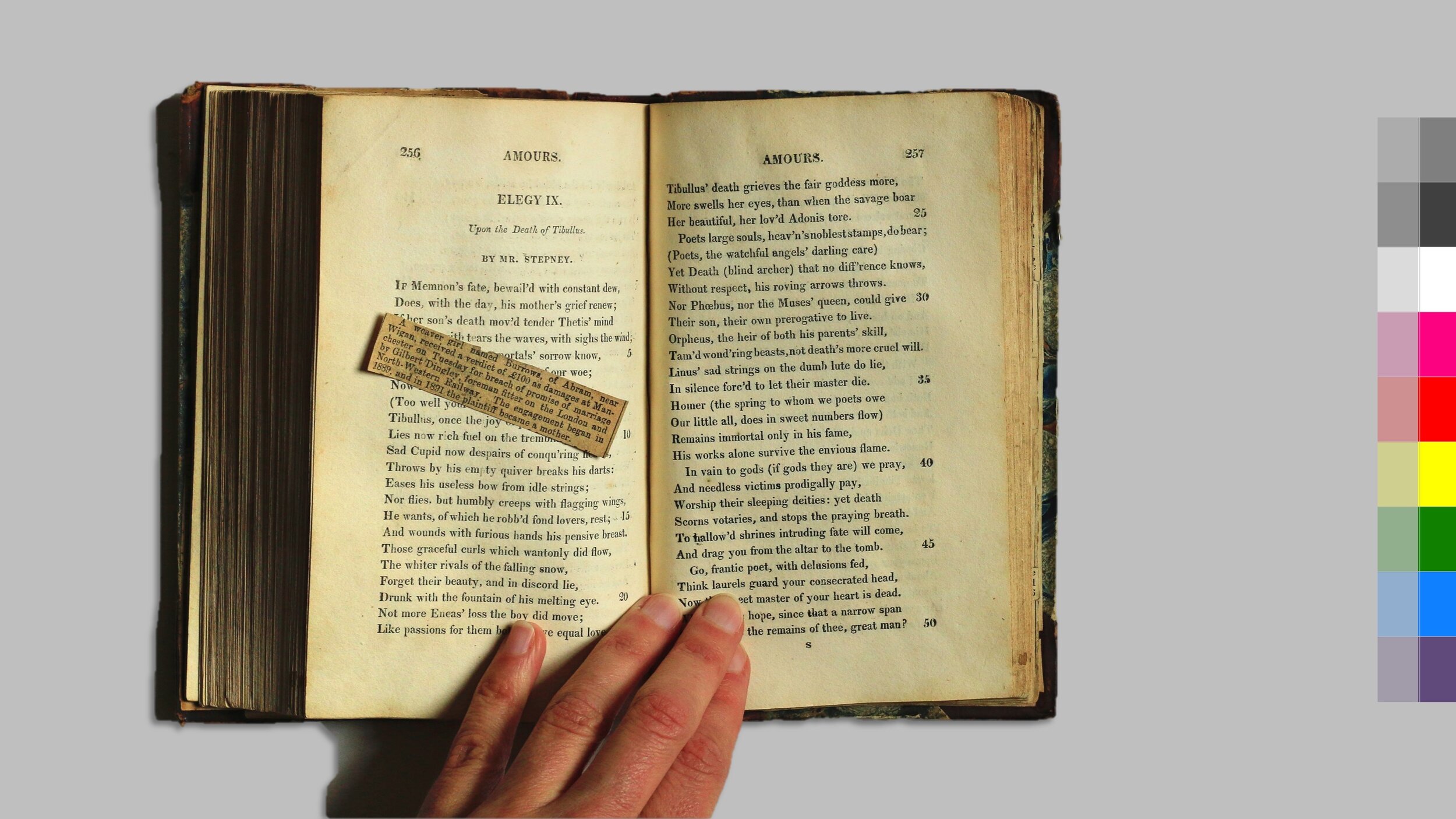

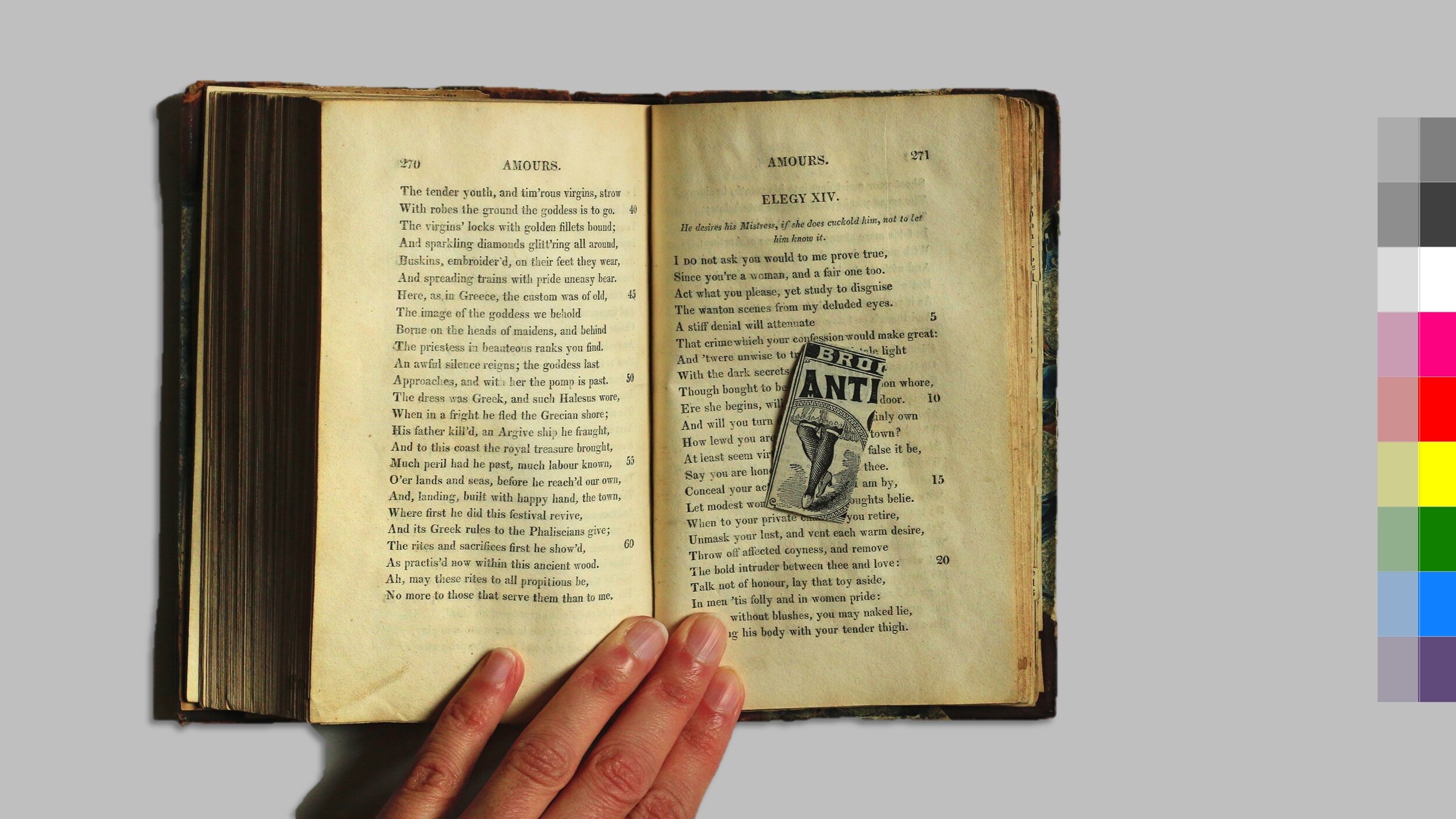

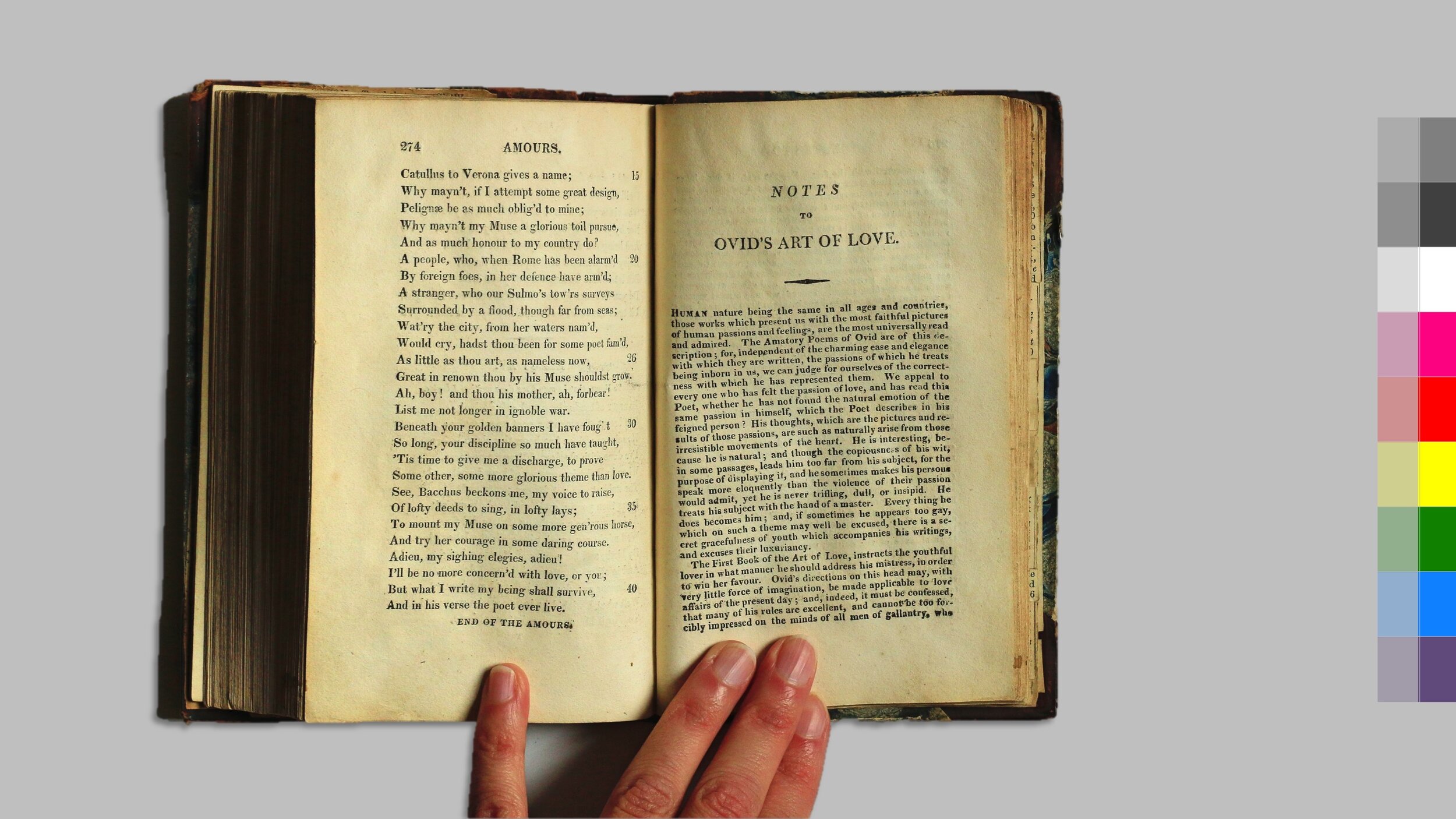

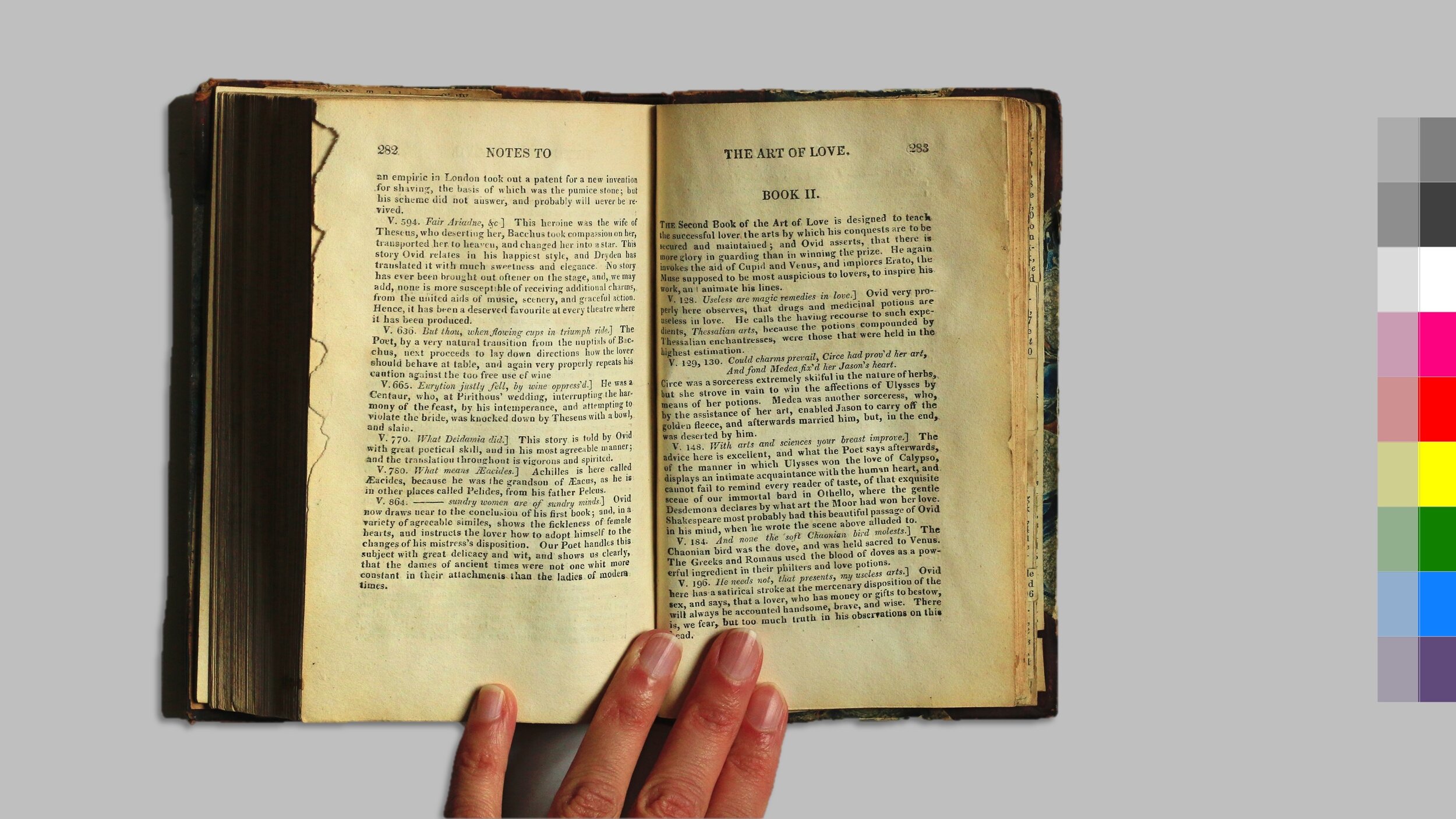

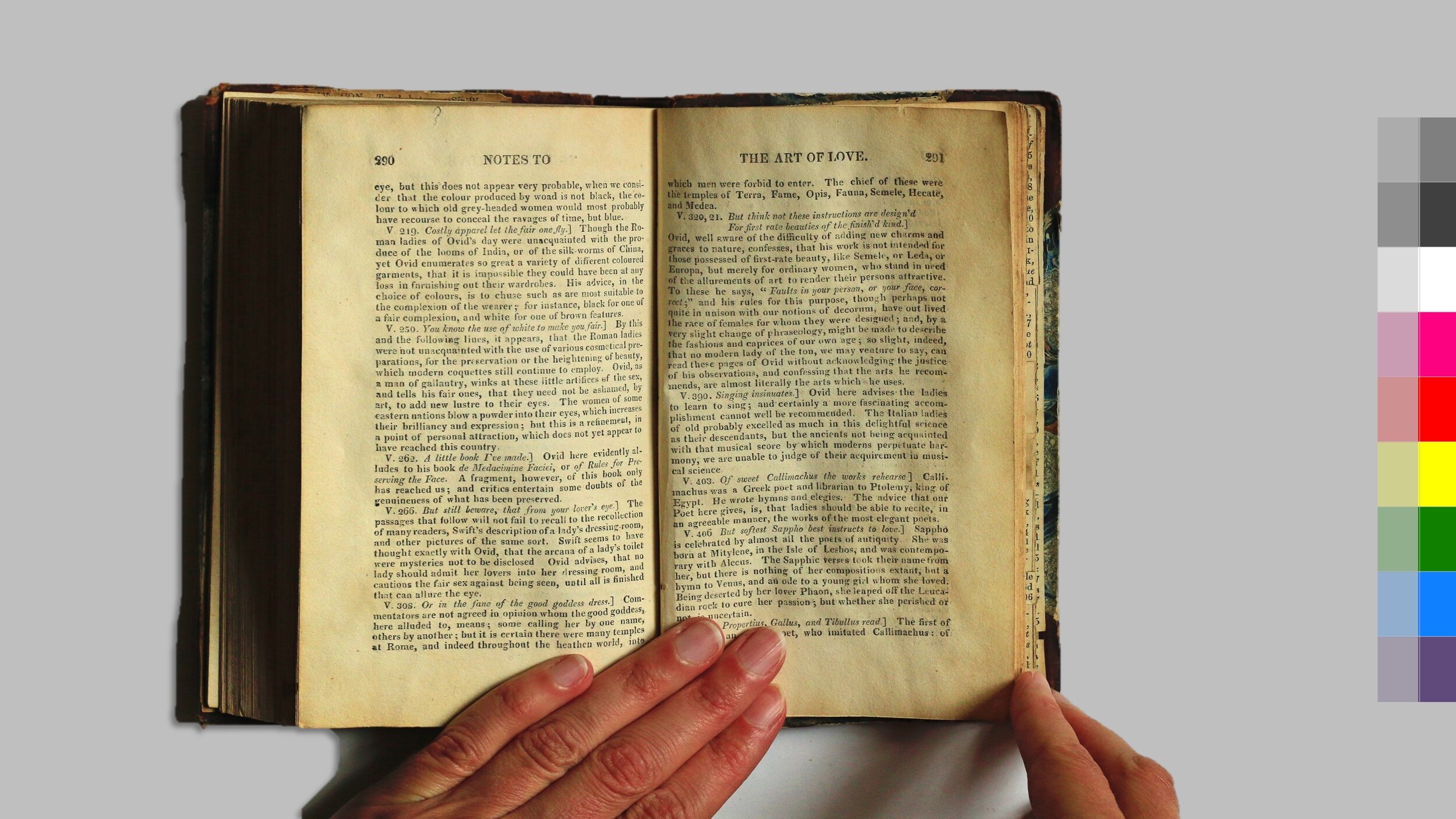

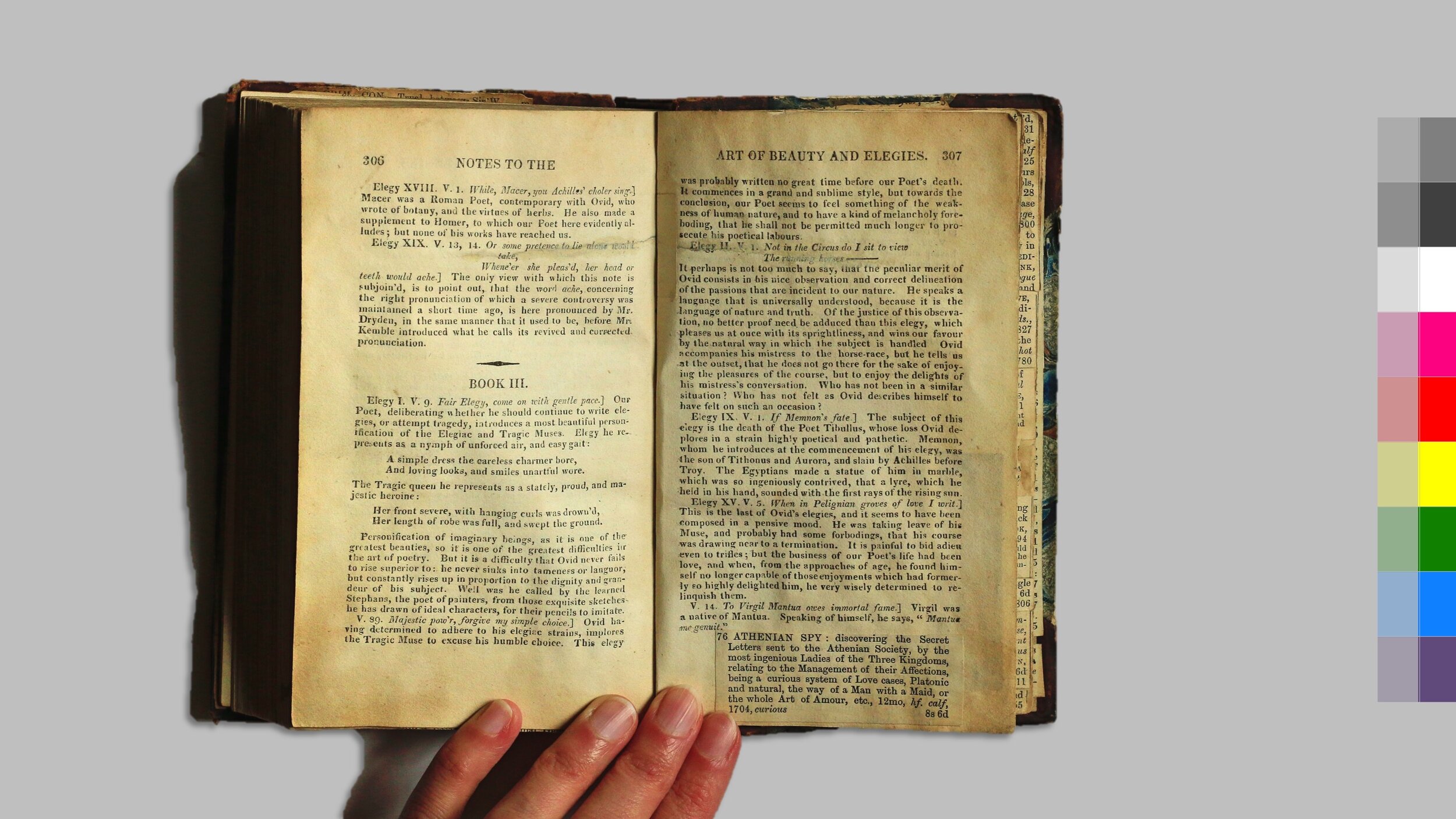

Since 2019 I have been collaborating with Adam Smyth to research and develop a new body of work. Our focus is an 1813 copy of Ovid’s The Art of Love. Adam has the book on long-term loan from a fellow professor—Katharine Hodgkin—who bought it from a flea market in Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire. Hers is the only signature in the book, dated Summer 1981.

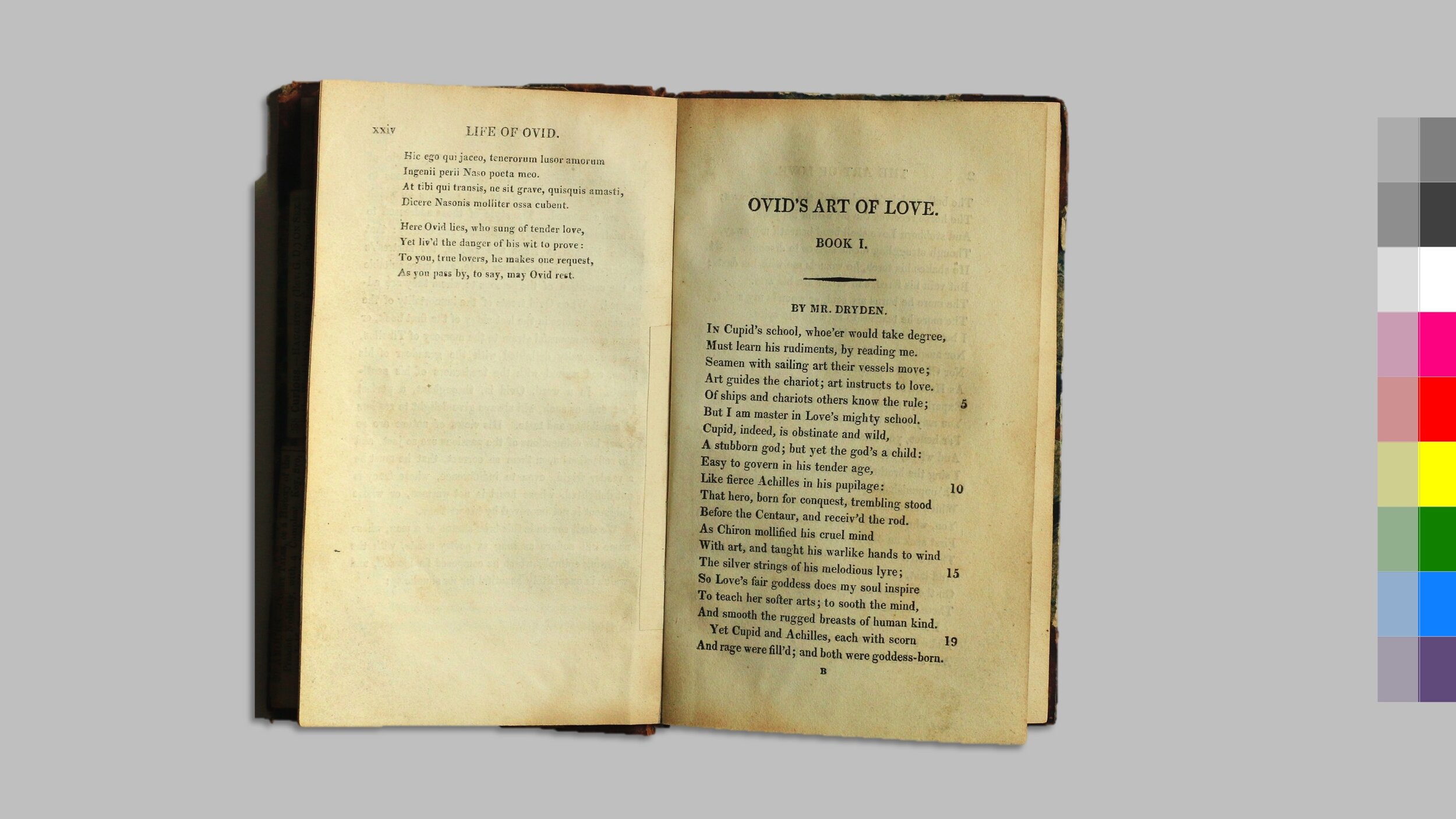

At first glance, The Art of Love does not seem particularly unusual for its time. It is leather bound, marbled and gilded. Various poets, including John Dryden, have translated Ovid’s original Latin poetry into English. The Portico Library’s collection includes several books of Dryden’s poetry and translations, notably a complete first edition set of The works of John Dryden, published in 1808.

The Art of Love by Ovid, translated by Dryden, 1813.

The works of John Dryden by John Dyden and Walter Scott, 1806. The Portico Library Collection.

Ovid’s poetry is in three sections:

Part one tells a man how to find a woman.

Part two tells a man how to keep a woman.

Part three tells women how to keep men (…from a man’s point of view).

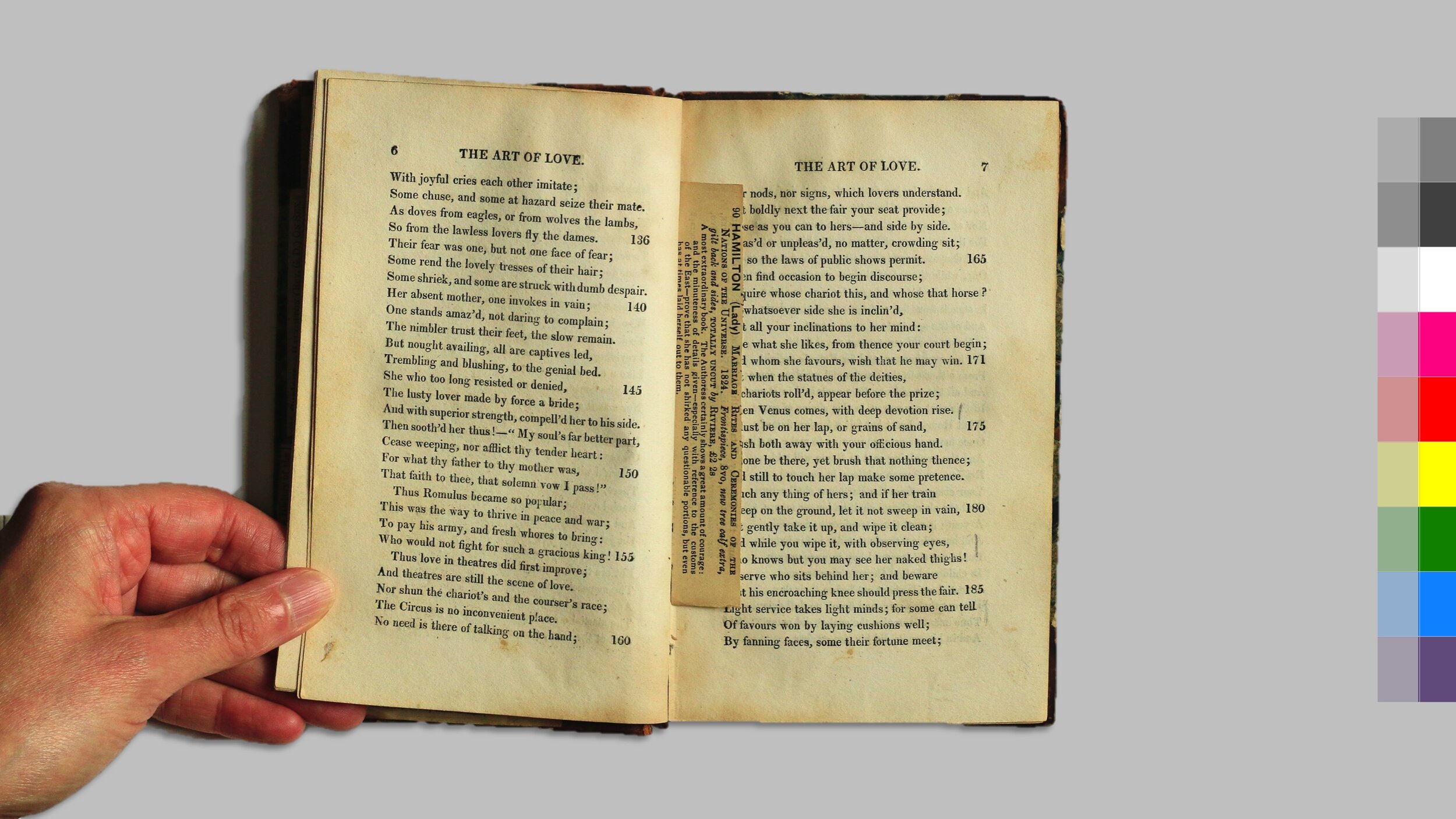

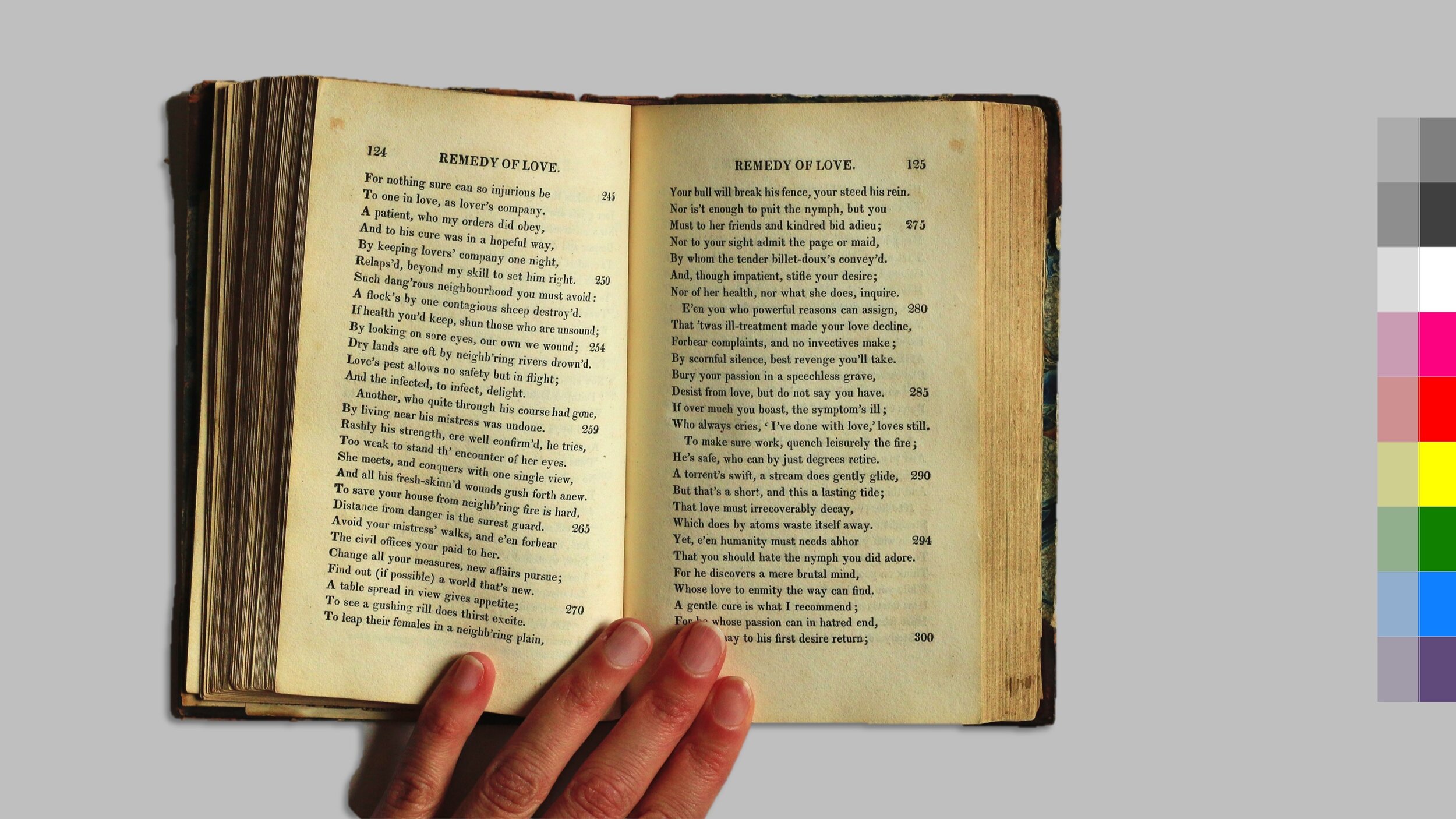

It often reads like the description of a military operation and is full of verbs like ‘strike’, ‘wreak’, ‘dishevel’, ‘mar’, ‘seize’ and ‘slaughter’. It is about conquest rather than love. It is misogynist. A contemporary reader might call its attitudes ‘toxic’. There is therefore a disconnect between the aesthetic qualities of this book—the way it has been bound, marbled, gilded, typeset etc.—and its contents; but this is the least surprising thing about this particular copy.

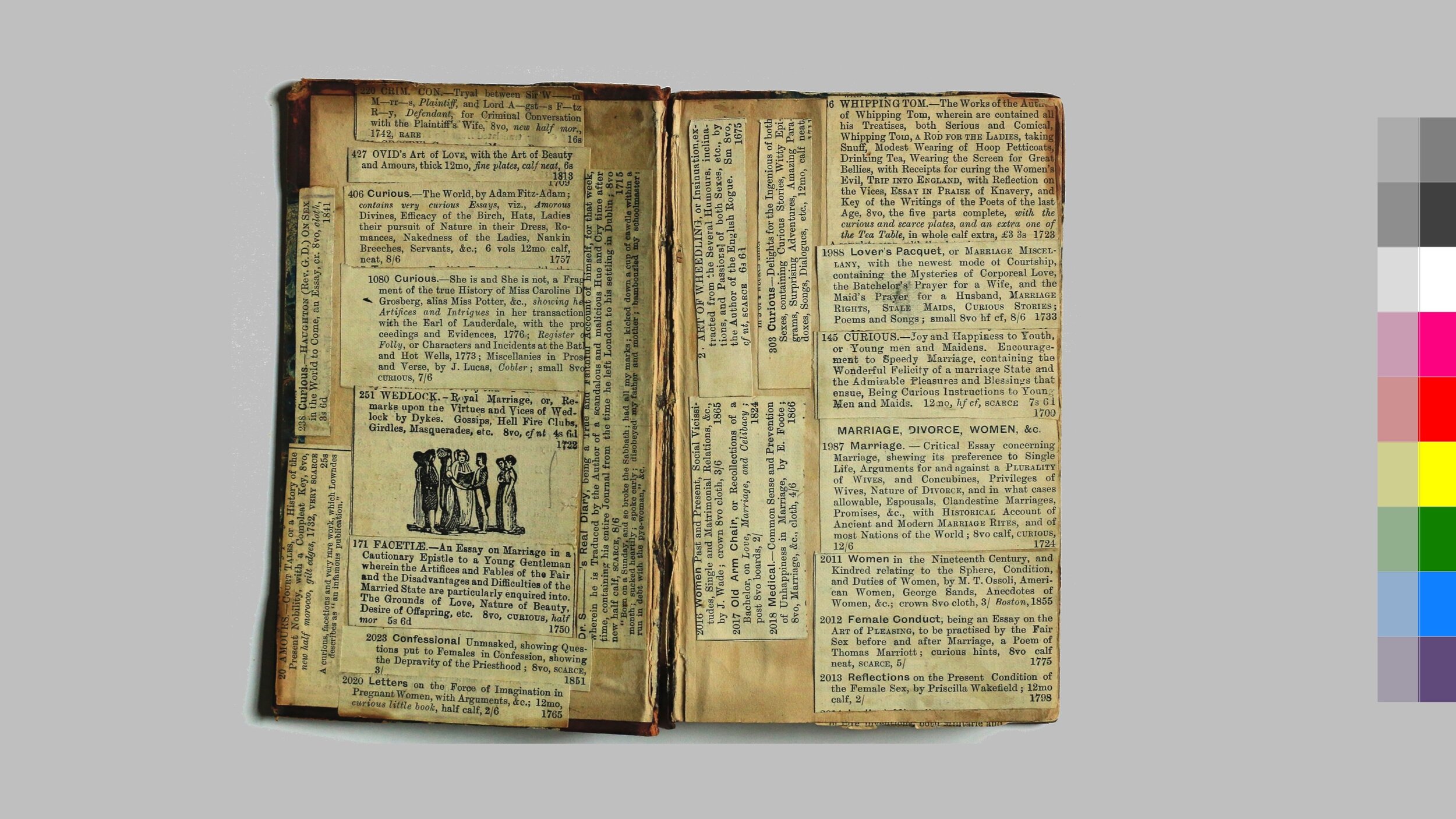

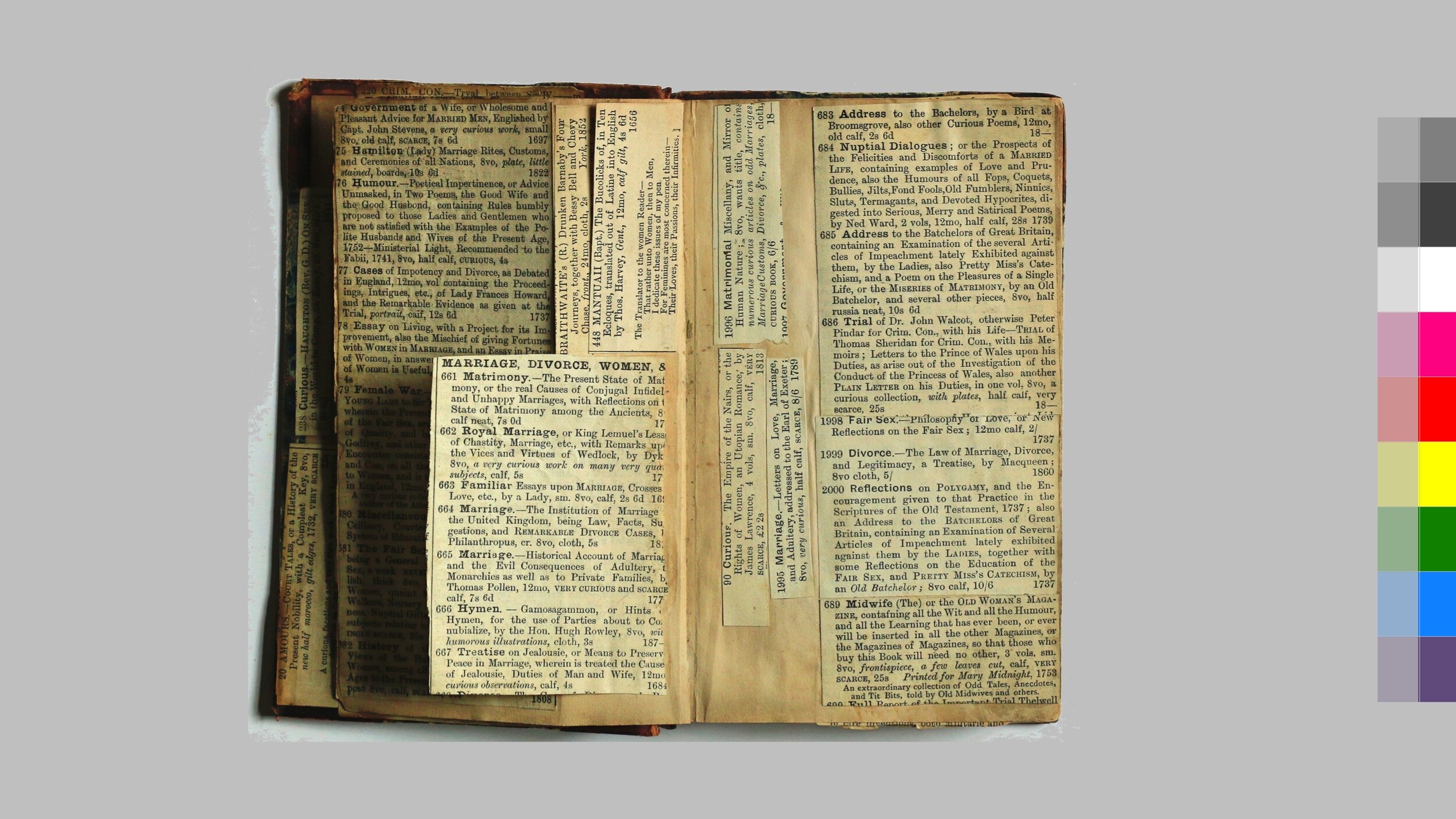

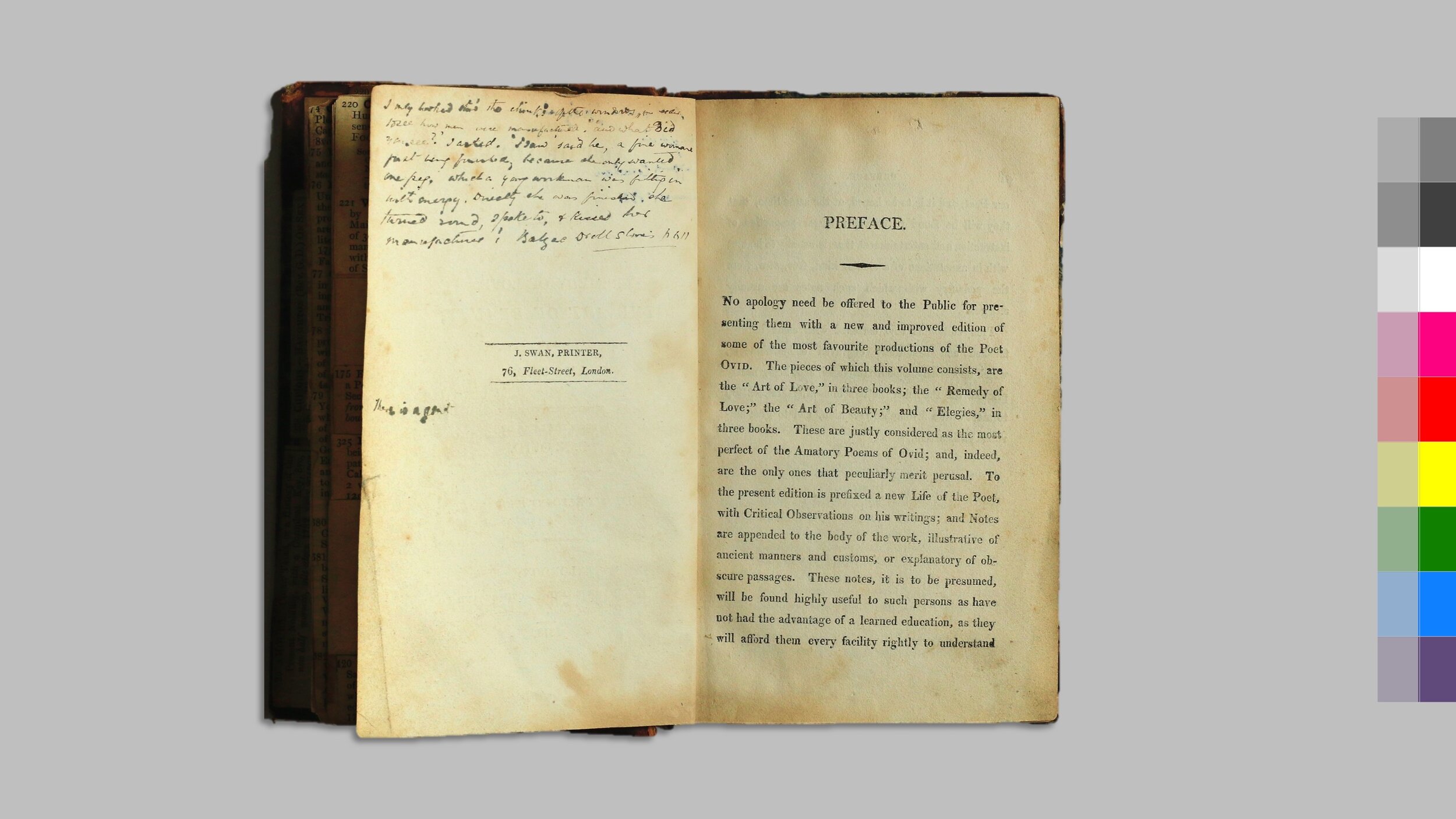

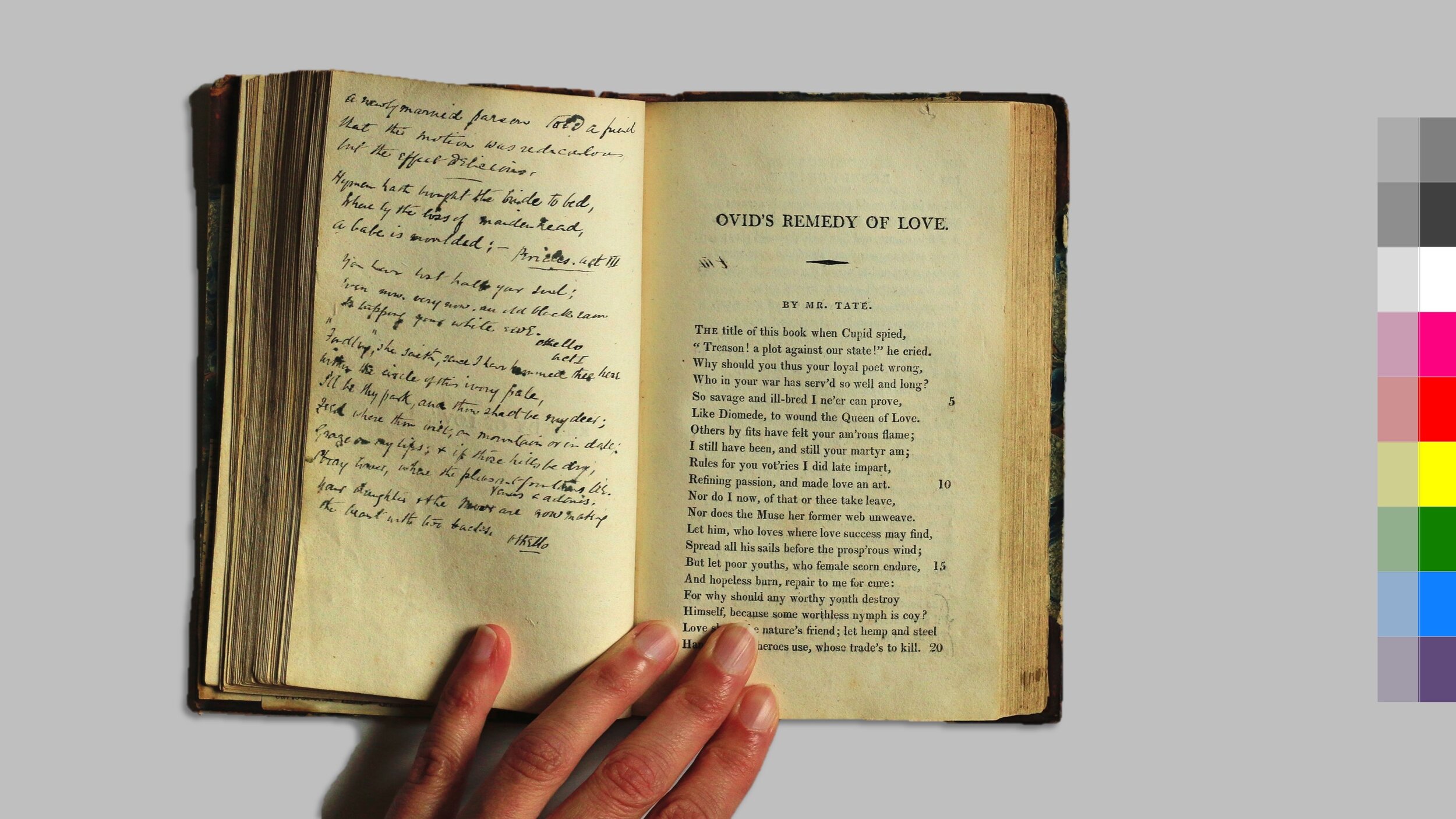

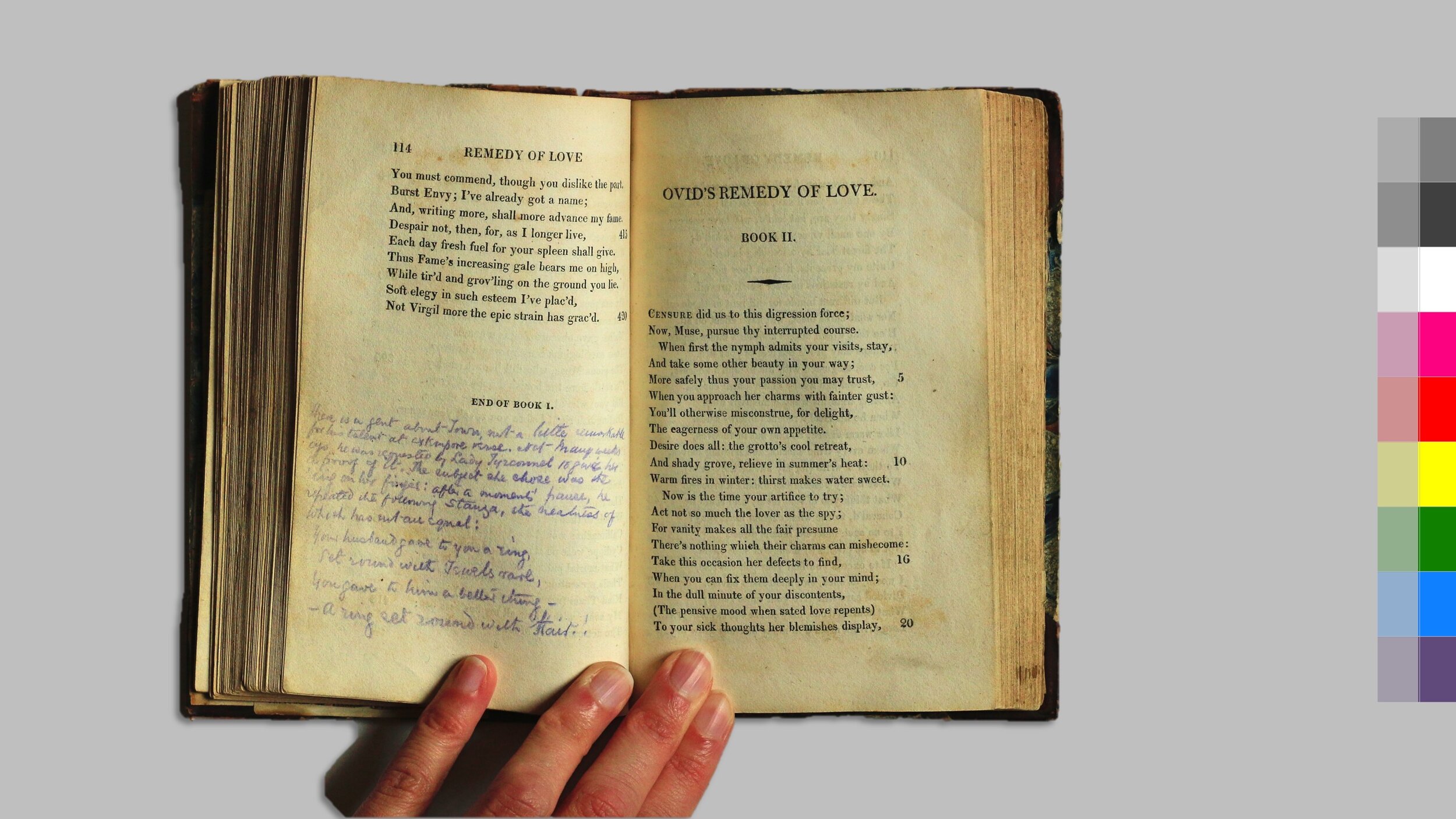

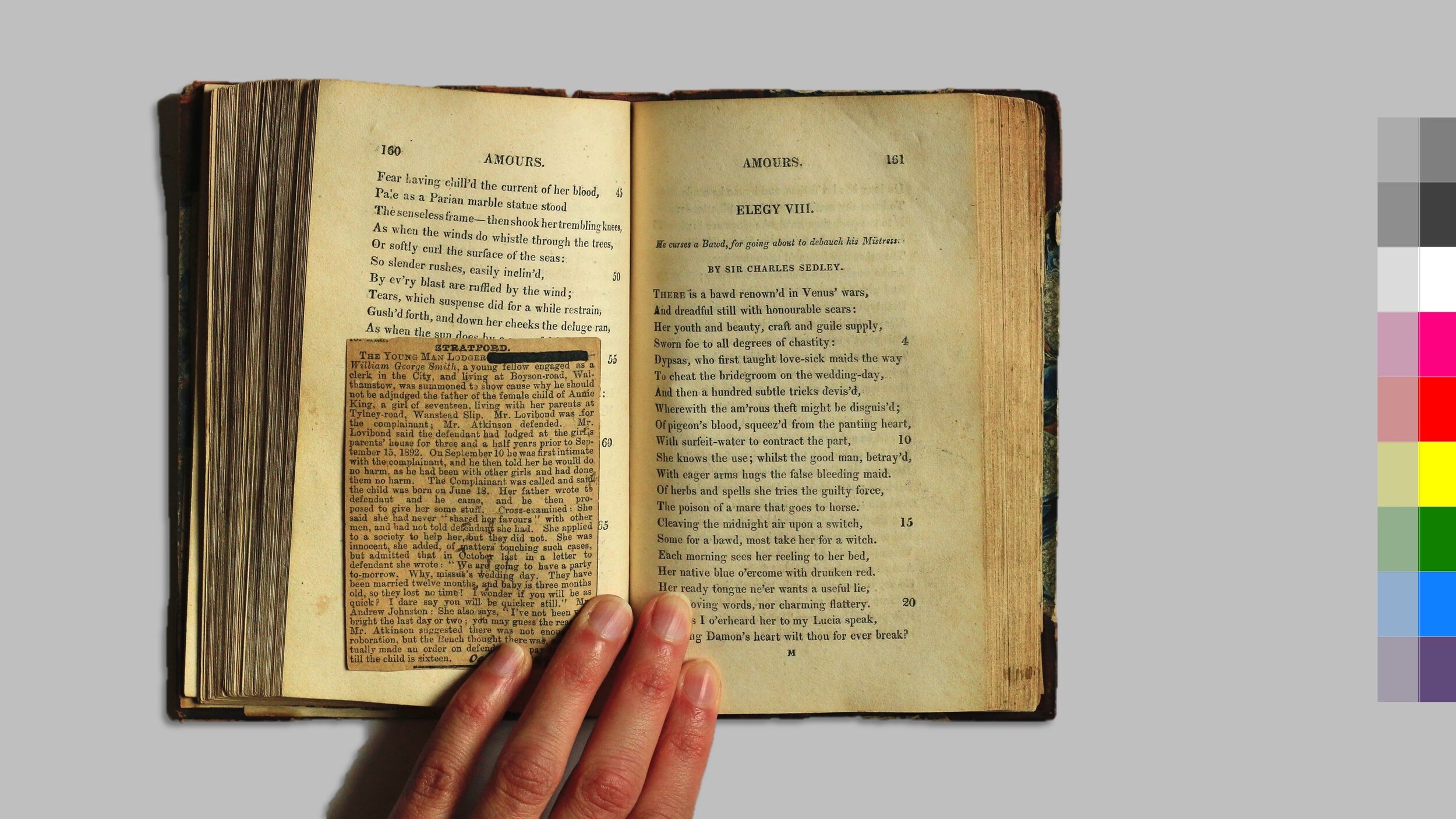

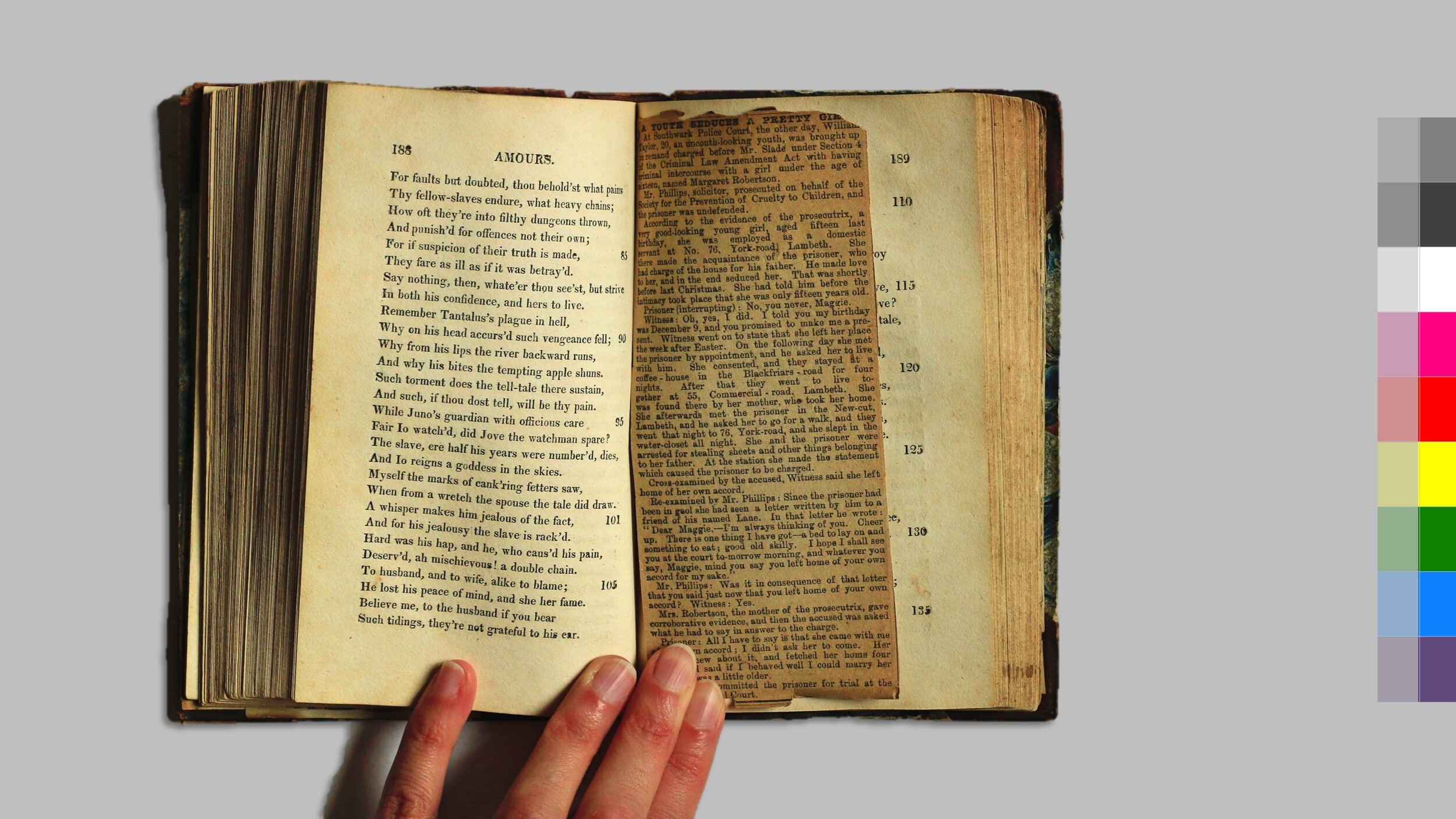

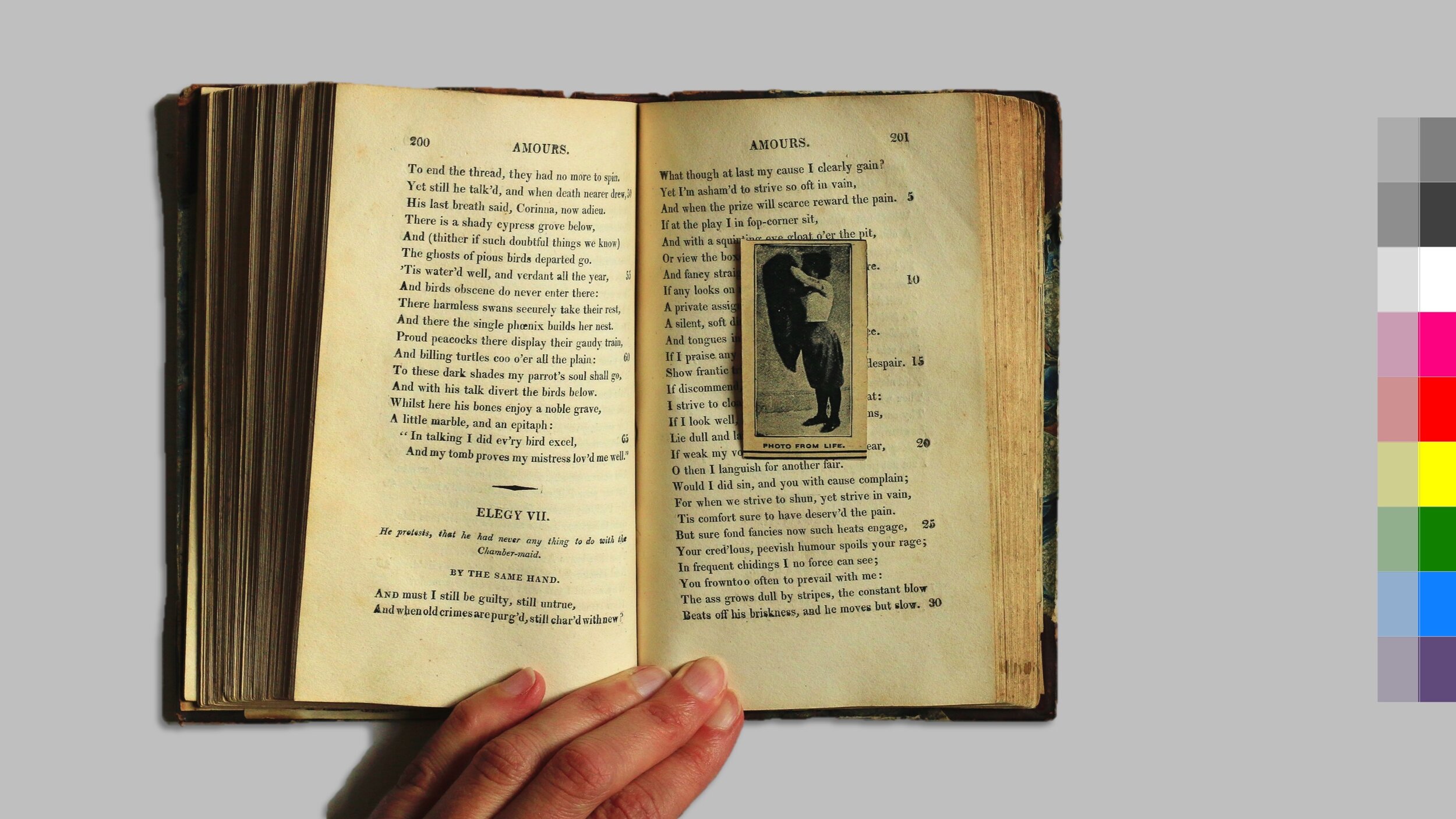

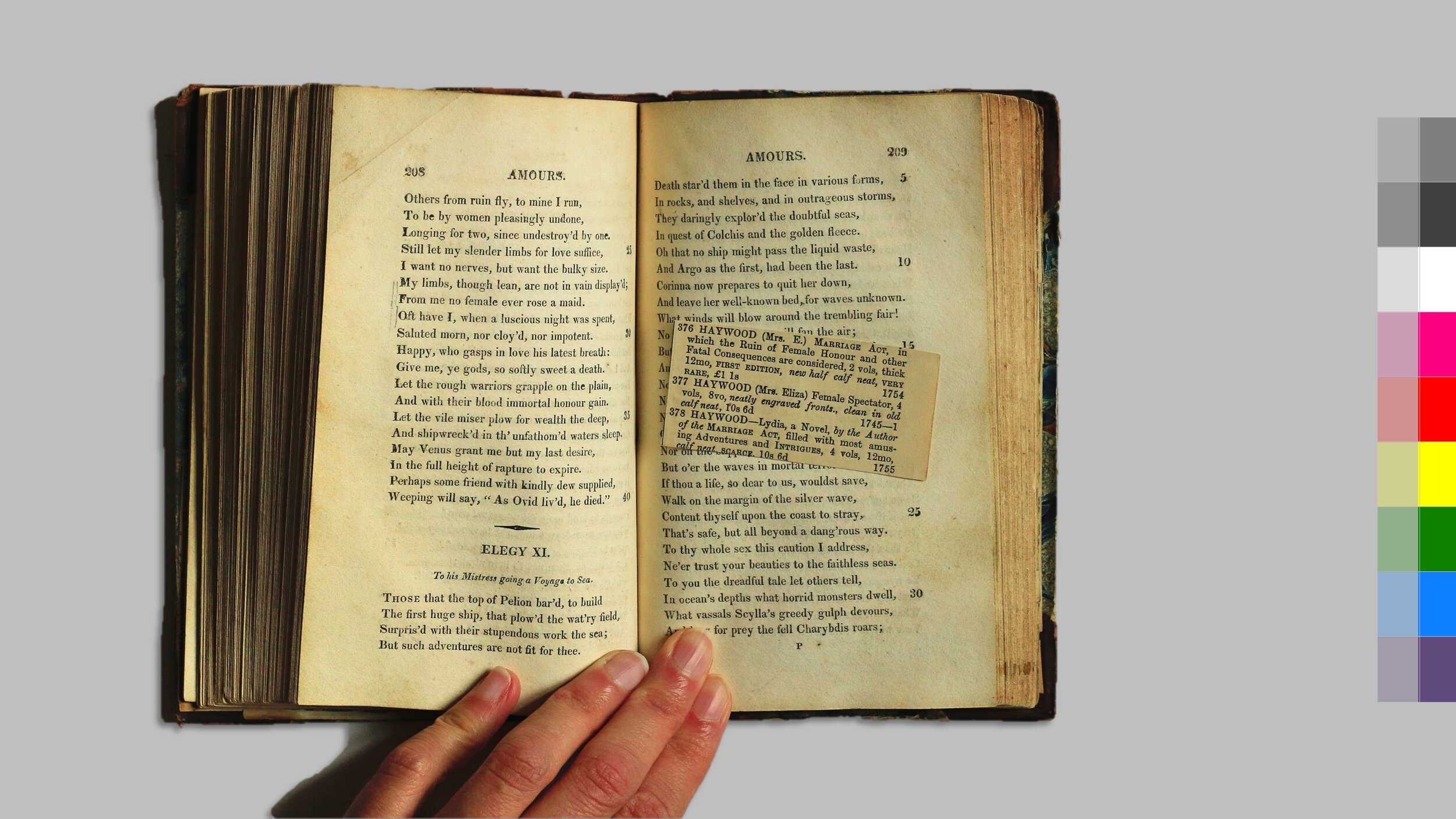

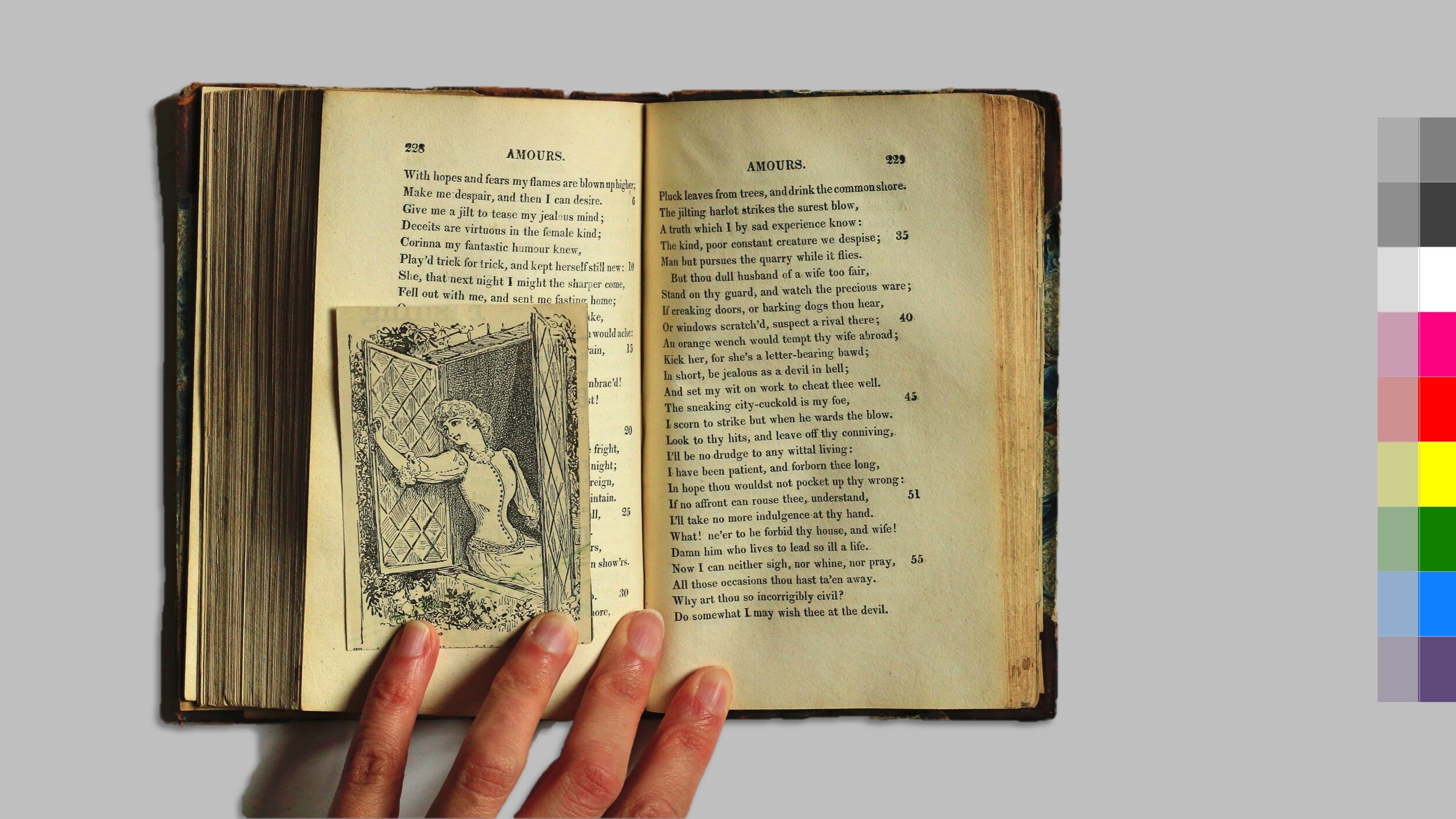

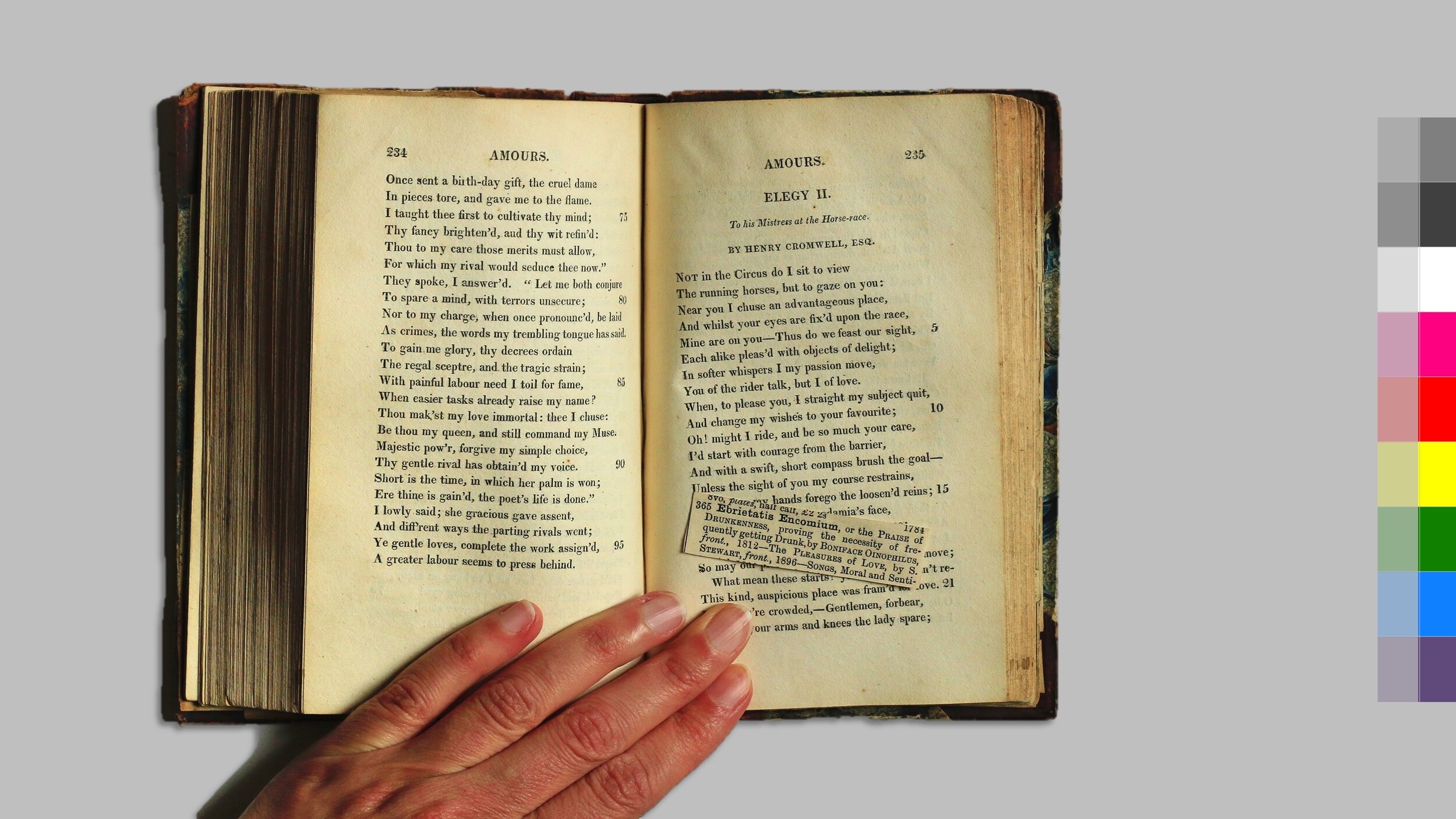

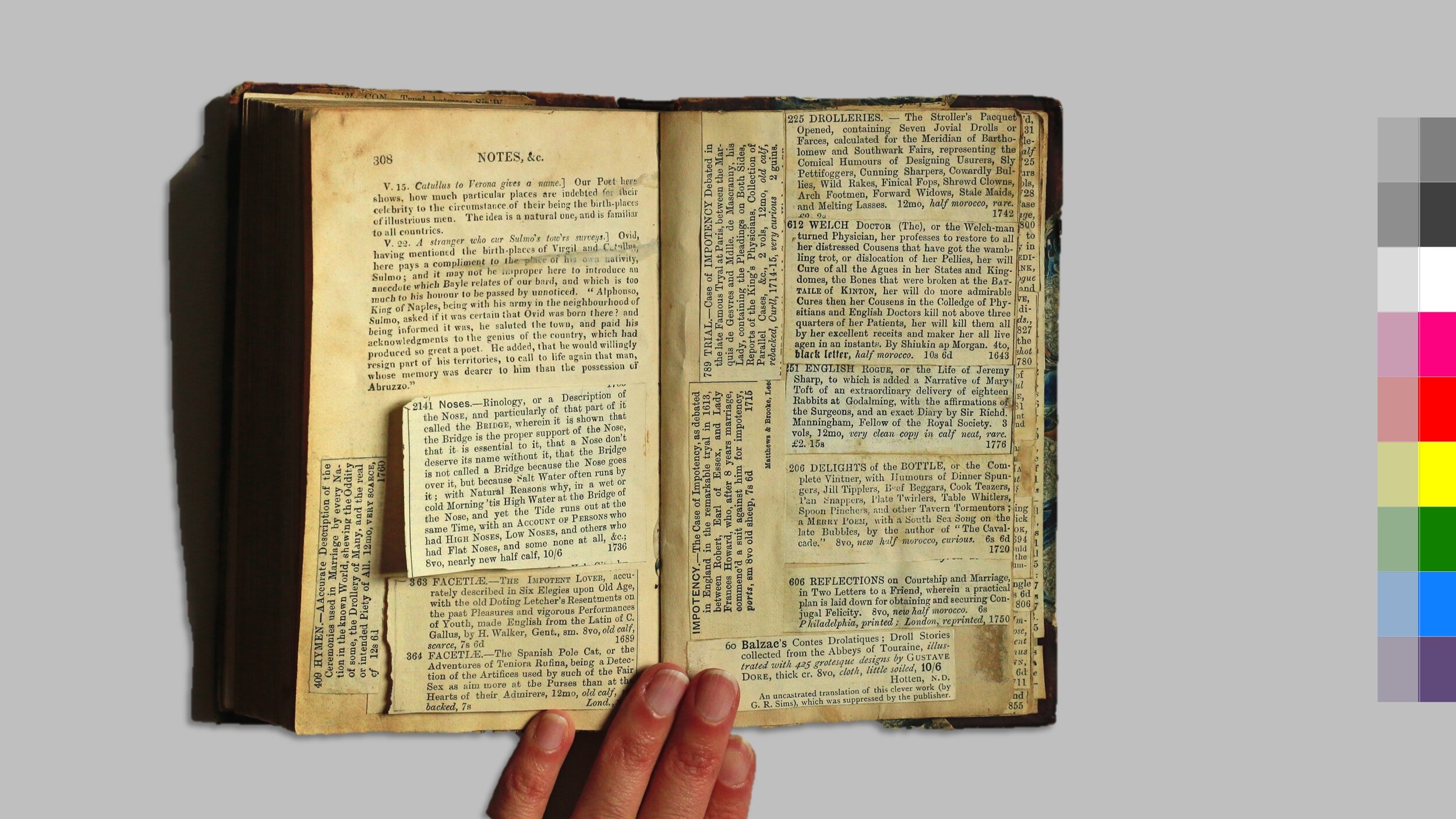

Over time, anonymous people have used this book as a kind of reference manual. It contains many inserts—some neatly glued in, others loose within the pages—as well as handwritten notes on the topics of love, sex, marriage, relationships and family, including Shakespearean quotes and dirty rhymes.

It’s an odd thing to have done (though there are histories of people adding to books–‘grangerising’) and it feels like it was a secretive activity, given the subject matter.

‘Grangerised’, or ‘extra-illustrated books’ as they are now more commonly known, are copies with blank pages left in them for the addition of illustrations, engraved portraits, prints etc, usually cut out of other books and sometimes also autograph letters, documents and drawings. The term derives from James Granger (1723-76), copies of whose Biographical History of England (1769-74), were bound up with blank pages in this way, although the idea dates back earlier to the 17th century, notably Nicholas Ferrar of Cambridge.

Page from James Granger’s Biographical History, extra-illustrated by Anthony Morris Storer with prints of Edward III dating to the 17th and 18th centuries. Eton College Library.

An example of 19th-century Grangerisation. Irving Browne, Iconoclasm and Whitewash. New York, 1886. Illustrated by the author. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Sisters Carrie and Sophie Lawrence extra-illustrating a book in their New York City workshop, ca. 1902. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Book-Butcher at Home by Henriot (Henri Maigrot). Originally published in The Book-Lover’s Almanac for the year 1893. Photo by Will Kirk. From the Sheridan Libraries, John Hopkins University. The caption reads: ‘The last of the Grangerites finishing his extra-illustrated copy of '“Nell Gwynn”, extended to 15,725 volumes folio by the slaughter of a book worth more than Nell Gwynn was paid for being Nell Gwynn.’

A unique example of grangerisation in The Portico Library’s collection includes a fold-out hand drawn illustration added to Conrad Gessner’s Icones animalium (1560). In addition, the Portico’s copy of The Discussion which took place between The Rev: Richard T. P. Pope and the Rev. Thomas Maguire (1927) includes blank pages which contain a mixture of handwritten notes, cut-out printed text and handwriting printed directly into the book.

Icones animalium by Conrad Gessner, 1560. The Portico Library collection.

An example of elaborate marginalia. The Discussion which took place between The Rev: Richard T. P. Pope and the Rev. Thomas Maguire, 1827. The Portico Library collection.

On studying our copy of The Art of Love, the main thing that strikes the reader (apart from the obsession over love, sex and marriage) is the sheer number of voices it contains, thanks to the various additions. These voices are our point of departure, inspiring the ongoing development of new work that encompasses sculpture, performance, image and text. Its first full-scale iteration, The Distressed Look will be exhibited in Leeds in Autumn 2020.

The Art of Love by Nicola Dale

L-O-V-E exists in the world

It’s there even if we can’t see it

It’s there even if we don’t know how to read it

It’s easily mistranslated though

Like when Ovid wrote ‘The Art of Love’

What he writes about is more like sport and war than love

In his book, there is always a point - an endpoint – to love

What happens between the sheets is the goal

Women are the opposition and the spoils to be spoiled

But in this version of the book, here,

(The only one in the world that looks like this)

What happens between Ovid’s sheets is far less important than everything that everyone else

does on top of them

Out here in the real world

Where the rules of sport and war do not apply

Should not be applied

What Ovid says is not the last word

There’s this person on top of that personThat person on top of this person

One voice on top of another, on top of another, on top of another and on and on

It’s impossible to read without hearing lots of voicesAnd if you can’t hear lots of voices, it’s very hard to love

Just let me say a little more about that, love

There’s a sculpture called LOVE that exists all over the worldIt’s by Robert Indiana and

Has been translated into several other languages

The letters L and O stand on top of V and E

A love square

If it were a triangle we would think...a love triangle, well there’s a bit of tension

But we don’t

Because it’s a square

And yet, and yet

There is a tension there

The O is tilted, wonky, slanted, sliding

Something has caught its eye

It’s distracted from duty, not standing up straight

It is looking sidelong at something we can’t see

What we see is its effect -Which is to make us look out past the sculpture

At all the places where the sculpture is not

Or where love is not

Or where it is hiding

Afraid of being spoiled

Ovid does not give a fuck about loveRobert Indiana did

Lots of other people do

I do too

I love you

Your voices

The Art of Love is by Nicola Dale, from an ongoing collaboration with Adam Smyth.

LOVE sculpture by Robert Indiana, on the corner of 6th Avenue and 55th Street in Manhattan, NY.

Nicola Dale is a visual artist based in Greater Manchester.

Adam Smyth is Professor of English Literature and the History of the Book at Balliol College, Oxford.